Wayne Thiebaud – In the shadow all the light happens

If I think about the work of Wayne Thiebaud (1920, US) I can not not think at the same time about the work of Giorgio Morandi. It is in both artists that I find a certain way of looking and composing enough within the canvas that it will speak without big flourishes. Of course, if we look close, we can see big differences: Where Morandi’s colors are very subtle and usually depict simple subjects such as vases, bottles or bowls Thiebaud is almost the opposite, with a use of color in its full potential and a representation of motifs that are more close to the image we could have of the United States food: cakes, hot dogs, lollipops… If Morandi was enclosed in his studio moving objects around and trying to get the perfect harmony among all of them, Thiebaud goes out to the world, sees, and then, goes to the studio and interprets these things by memory.

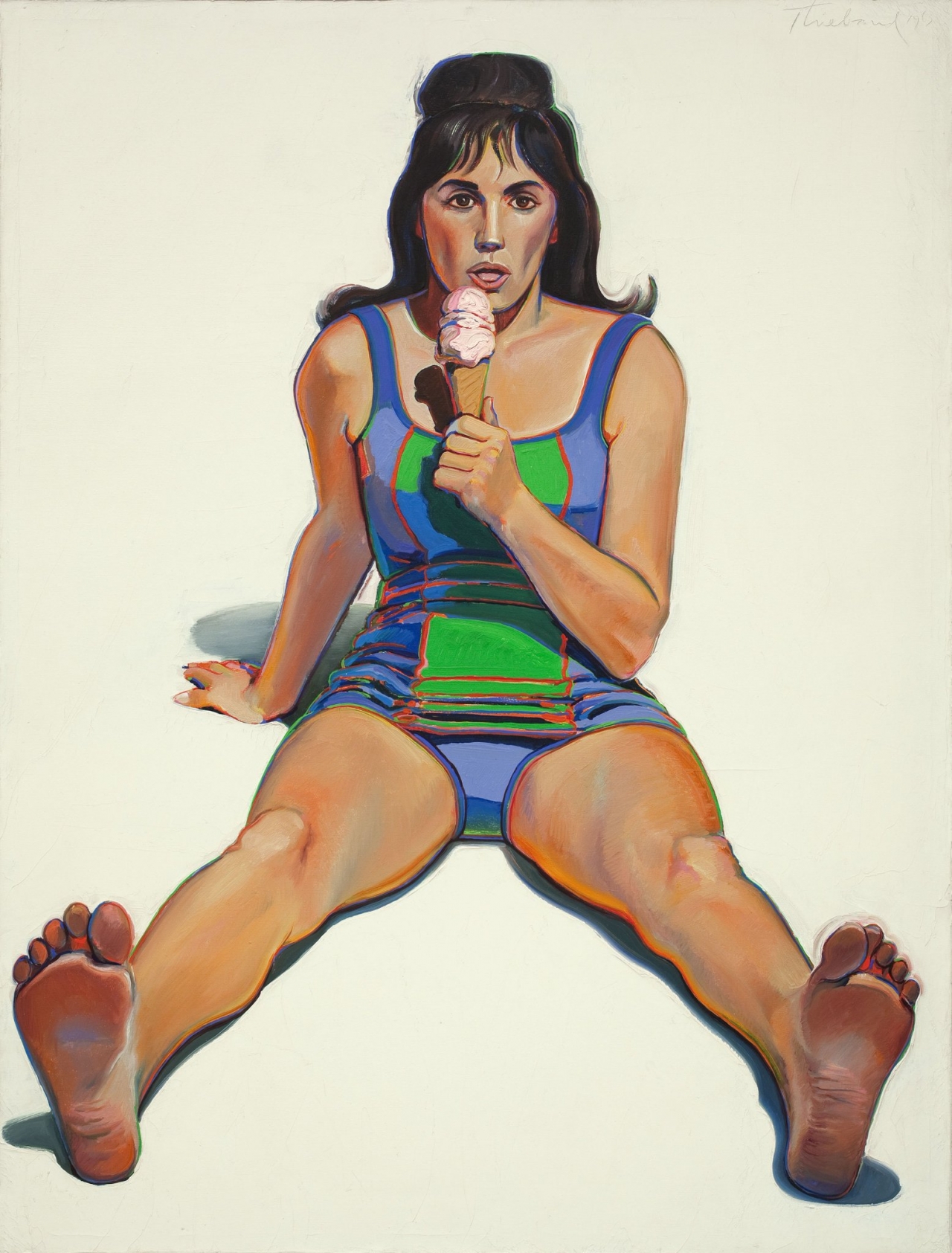

Until the 16th of September the museum Voorlinden is hosting the first-ever European retrospective of the work of Wayne Thiebaud bringing together around sixty of his works from 1961 to 2018. Walking through the exhibition we can see that the questions about color, light and compositions are quests of a lifetime that the artist still develops and tries to solve (or give his opinion about) within different motifs, being the most famous mouthwatering depictions of cakes, ice creams and hot dogs, but being explored with the same interest and intensity in portraits or landscapes. The most interesting aspect of Thiebaud work might be his use of colour, that most of the times gets accentuated by very clean backgrounds, allowing us to focus in the main represented motifs. A good example for this might be Girl with Ice Cream Cone (1963), where the subject is as simple as its title, but it is in the richness of the outline of the girl, contrasting with the white background where we can see how he gives us colors that might exist in reality and we are just not able to appreciate.

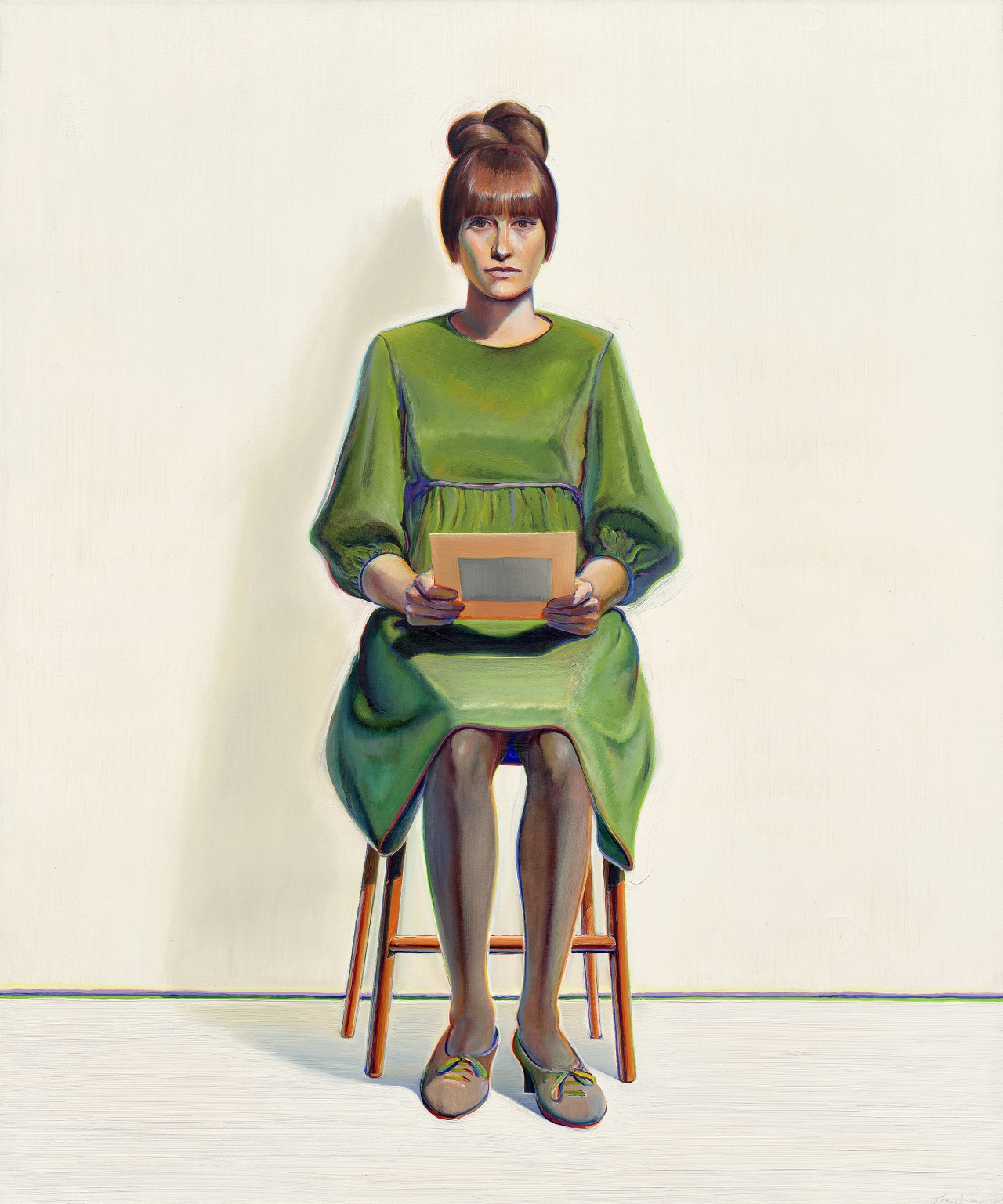

The interest in these works by Thiebaud it is not only located in the final outcome, but also on the process. He does most of his work by memory (with the exception of the portraits), but with a lot of previous drawings. Once the painting starts, this can last for years, as he does not have a problem to look at things for long periods of time. A good example of this can be the painting Green Dress (1966-2017), which took 51 years to be completed. In a world where everything goes faster and faster, art included, it is nice to find from time to time cases as the one of Thiebaud, who worked as a teacher until he turned 70 and that took these classes as an education for himself, both giving to younger generations but engaging with them for his own work.

Without any doubt my favorite painting in the exhibition is Smoking Cigar (1974), a very small depiction of a cigar that David Anfam suggests is a clear reference to Mondriaan: It is an off-white square, with a thick line along the bottom, parallel to the bottom edge, and a thin one on the right, parallel to the side. So far, so Mondriaan-like. The difference is that Thiebaud’s thick line is a cigar, its juicy brush strokes wonderfully evoking the papery dryness of its outline, the powdery quality of the ash at the end. While the thin line, wavering and delicate, is a light plume of rising smoke. The formula for a Thiebaud, partly at least, is geometric structure plus a wizardry worked with the brush.

An amazing overview of an artist that is starting to get recognition in Europe (he had another exhibition in late 2017 in White Cube London) and that if I could find something to criticize that would be the lack of benches in the space, since these paintings are asking for long sitting in front of them.