Trying to forget myself

an interview with Isabel Pagliai

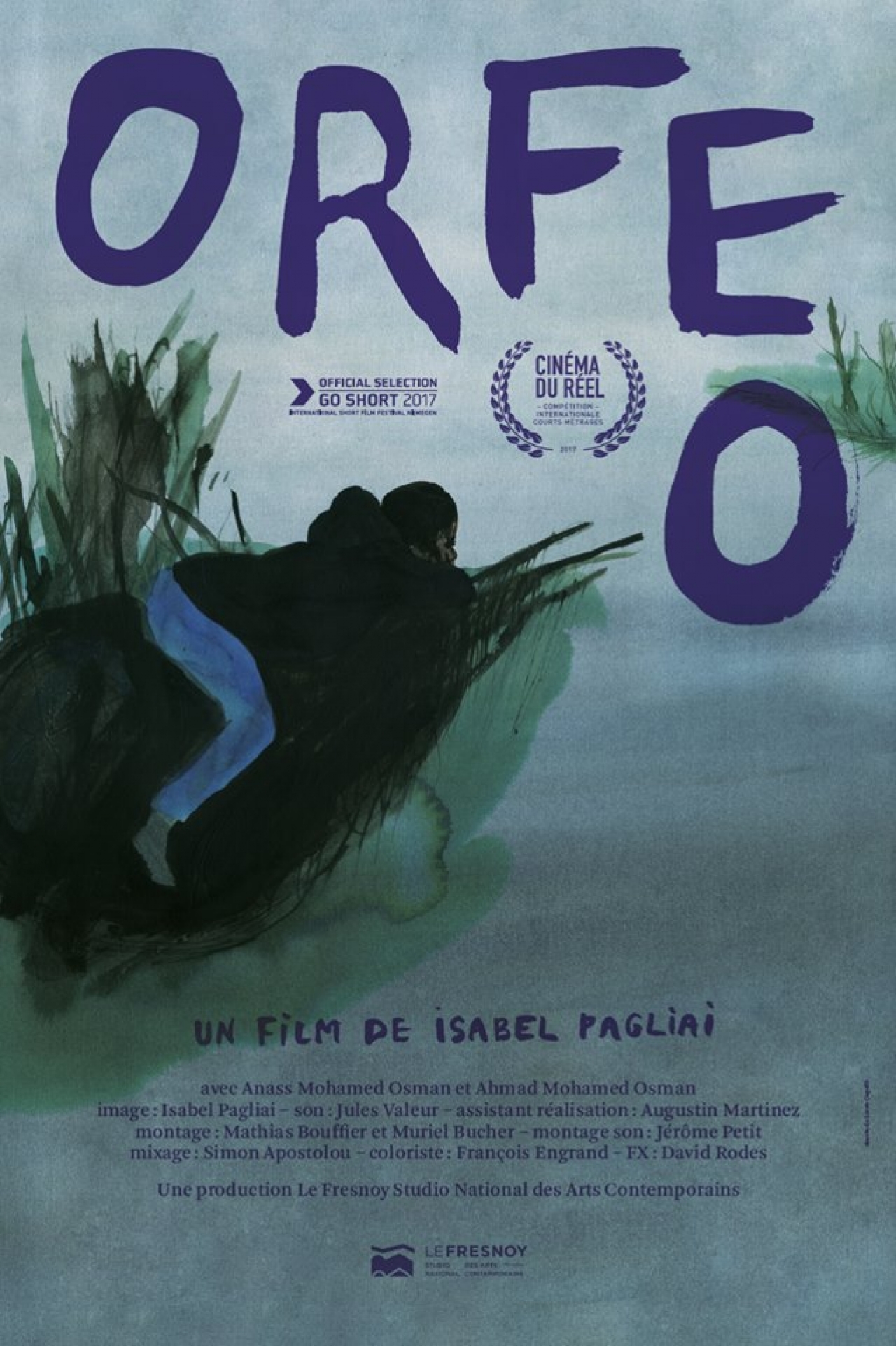

Isabel Pagliai makes very powerful films; with her mostly steady camera and child actors, she manages to create a hypnotizing world. It’s hard to point out though what her films evoke in the viewer or what they are exactly about. Reason for Mister Motley to talk with Pagliai about her successful first film Isabella Morra and her rather different new short Orfeo. Orfeo had it’s international premiere last week at the Go Short International Short Festival in Nijmegen.

Mathieu Janssen: In Orfeo we see a river crossing in a forest at night. There are people walking in the distance, and there’s a kid, alone, sitting and throwing stones. I love the film, but I wouldn’t know how to explain to someone else what the film is about. Can you tell me something more about what your mysterious latest film is about?

Isabel Pagliai: To be frank, I don’t really know… [laughs] I really try to tell stories but there is something that’s holding me from it. The idea behind the film is that I wanted to shoot a place that was dear to me and of which I am now foreign. The forest and beach we see in the film are near the French-Swiss border – I went there as a child to escape family tensions. It was my place. I spent hours there, without moving, contemplating the opposite shore and wondering what it would be like to cross the river and go to the other side. Although I was sad, I have many positive memories from those moments. It was a period in my life where I felt free. I was alone but alive. It was also a time without stories.

When I started this project, I had the idea of a stuttering voice that would have embodied a character. But this voice-over didn’t work, so I completely removed it during editing. The film thus became a more abstract and a mental journey, but also more in tune with what I felt intuitively. I simply couldn’t put words or a narrative on it. When I make a film I substract a lot in my process, but in the end I prefer a film with lack of explanation over a film that explains to much.

MJ: What do you mean with ‘a time without stories’?

IP: For adults everything has a story. A context to which things relate. As a child you could still be free of mind and body, and totally vanish in your environment. I still long to this feeling of freedom.

MJ: Is that why you work with children a lot?

IP: [laughs] You could say it’s kind of an obsession of me. I find them inspiring and powerful. Children can forget themselves. And maybe the only moment when I can be a child is when I’m filming. Then I forget the context of the world I’m living in; I forget I have a body and I don’t care if it rains or that I’m hungry and didn’t sleep.

MJ: Although the title of the film, Orfeo, is reference to a famous story, your film is without a story.

IP: Yes, it turned out more as a poem. I’ve worked several times with director Damien Manivel as his co-scenarist and director of photography, and for him I can write narratives. But for my own films, I don’t feel a narrative. I try to tell what I want to tell in a different way.

MJ: How would you describe that way?

IP: [long silence] In my pictures I try to depict something surreal and poetic, and evoke a sensation of hypnosis in which you forget time. On the other hand is a gaze – to look at something – very temporary and something we forget. This tension between the plain images that I show and the state of hypnosis that they can provide interests me.

Also: I can’t shoot what I can’t feel. I’ll give you an example: I can’t shoot people walking at the moment. I mean… I’ve tried but I cut everything out during editing. I just don’t have the desire to see people walking at the moment. No walking in my movies! [laughs]. These limitations also produce a situation in which I create strange stories. I would describe my films more as a world of sensations, with multiple layers that create some kind of density.

To come back at your earlier remark about the title reference to Orpheus: I’m indeed not adapting this story, but I like to use it as a starting point. The original story makes me think of things that are important for me. I use these things, like the idea that a look can cause death, or on the contrary, that it can revive. It’s like a pre-text, or a motive, to my own story.

MJ: Something different: I would say the font color is remarkable.

IP: [laughing hard] I like the colors, they come to me even before filming. The color sets the atmosphere, the tone of the film; it imposes itself. Color is a very strong narrative element for me. In my previous film Isabella Morra, the font color was red, and when I started working on the film I already knew that exactly this red should be the color. It’s the same with Orfeo, before shooting I had the color in my mind, and the fact that the film takes place at night.

MJ: Orfeo is a personal film, and you are telling your own story. Isabella Morra is a very different film. You’re working between the lines of fiction, documentary but again with an existing story – that of Isabella Morra* – as a starting point. In the film we’re following a couple of kids in a poor neighborhood, talking like grown-ups with violent language. Who’s story are you telling in that film: Isabella Morra’s, that of the children, or your own?

IP: It’s mainly the story of the children. I wanted to show how they are kind of resistant to their violent environment, and their language is a part of that.

It has a beauty on its own. It tells their story of how they cope with their situation best. I used the story of Isabella Morra, just like in Orfeo, as a canvas – and not as a story I wanted to adapt.

MJ: Is Isabella’s story important for you as a person too?

IP: Well, I guess I also find it not easy to live in this world. Society is hard for many people, and for these kids living in poor areas in particular. Isabella lived in hard times too: those of the Spanish inquisition. That’s one of the reasons I chose her story as a pre-text, but I tried to do something different than in the stage-play of André Pieyre de Mandiargues. He showed Isabella Morra as a classic nobel women. I love that piece and the language, but unfortunatly there’s a lack of new voices in France, when it comes to cultural representation of kids living in poor areas. In my film, I wanted to show the nobleness of these the kids too : they also are Isabella Morra.

MJ: And Isabella was stuck in her situation, held by her brothers, like you were stuck as a child, with the strict education of your parents?

IP: You could say that… Actually, making movies is a good way for me to open up myself. Shooting a film lets me meet people, and get in authentic contact with others. It’s my way of making a real connection with the world.

* Isabella di Morra (ca. 1520–1545/1546) was an Italian poet of the Renaissance. An unknown figure in her lifetime, she was forced by her brothers to live in segregation, which estranged her from courts and literary salons. While living in solitude in her castle, she produced a small body of work, which never circulated in the literary milieu of the time. Her short and melancholic life ended when her brothers