THE TAMING POWER OF THE SMALL

On a few works by Nishiko.

This is Nishiko. A small, frail Japanese girl. Her appearance harbours a very strong, original and independent mind. The backpack is actually a mobile studio she used when she temporarily didn’t have an ordinary one. She also organized mobile shows in it with works by different artists.

I’m not sure about the status of this photo. It could well be a metaphor for the associative mind that can make art out of anything, or it could be just a snapshot. It’s not really important, but it shows the way Nishiko is taking us with her into a world where the borders between ‘art’ and ‘not art’ are blurred. This is typical of her attitude with respect to circumstances and possibilities – she will always arrive at a different solution, often concerning matters no one else pays attention to. In this case the ‘studio’ only bears a passing resemblance to an actual studio and one thing that is definitely impossible is being inside it, in much the same way that it is impossible to walk in a show-box landscape a child has built inside a shoe box. One can only look at it. In a similar way this studio can only be seen from the outside looking in which, if you will, alludes to the way the White Cube is, in a sense, closed off from the ‘real’ world. On the other hand this special white cube is portable and can easily be taken anywhere and in that way it does function in the real world after all, but it’s such an ambiguous affair that one is never quite sure where one is, in which world, in which context. Finally, it addresses a concept of the artist as a nomad who doesn’t really live in her studio and is only an artist when she is working there. Rather, she is always carrying her artist’s mindset with her; everywhere she goes, 24/7. Being an artist is not something you can turn on and off at will, it is a state of mind that is always with you (“Ich kenne kein Weekend”), that, in a sense, is you. It is even a physical thing, you carry it on your back like all luggage, but then as a metaphor; the backpack is really part (or an extension) of Nishiko’s body, or rather mind-body, which of course is an artificial separation we have come to cope with since the development of Western civilization.

In Nishiko’s work events, texts and objects are never taken for granted but everyday things that may happen to her or which she happens upon while doing or considering other things. They are taken out of their original context and questioned, which entails changes in meaning and appearance. Nothing is familiar and the viewer has to deal with changes to the degree that they may feel like being stranded in a different world – a bit like Alice in the sense that Nishiko introduces and partly guides us into a world of fiction where fact and fiction are related in a different way: a factual moment can become fiction in a different narrative or, conversely, fiction may be (loosely) established as fact. Also, facts can become different facts with a connecting fictional narrative that complicates things further.

Years ago, Nishiko accidentally burned part of her left arm. This is a classic example of an incident she may or may not use in her art practice. In this case she did. She had the outline of the burnt area tattooed on her arm, emphasizing the physicality of the work. In a sense, again, it literally is (part of) the artist’s body. So here we have an artwork with many specific characteristics: a real life event is shifted to the art context. The form of the outline is arbitrary because it follows a random structure that has now acquired meaning. A temporary image has been transformed into a permanent one – while the burn has disappeared over time, the outline remains – and the permanent one is really a memory or echo of the original one, although at some point no one except the artist herself and the people who know about it will be able to recognize that memory as such. Over time the tattoo will in turn become the primary image which seems then totally devoid of meaning as its shape does not reveal anything of its history, except that there must be a history, a story, a lost narrative connected to the image, a reference, but to what? It used to function as a ‘definition’ of a piece of burnt skin, but as the burns faded away it became a definition of what? Of nothing? Of itself? And if so what could that possibly mean? In this way the work becomes its own myth. So it’s also a work that changes with time, nothing is set in stone; everything is fluid like life itself.

This work is also the result of a common physical event: a filling fell out of one of Nishiko’s teeth and was enlarged and transformed into an autonomous object, a kind of (almost literally) tongue-in-cheek ready made. Presented as if it were a sculpture, it consequently radiates an aura of fine art and could well pass for an abstract piece from the late fifties or early sixties, were it not for its modest scale, almost a miniature sculpture, conjuring up associations with a model and also adding a satirical flavour to the mix.

In a later phase the work shows a stunning reversal of form as well as a relatively impressive enlargement that, in turn, will be greatly surpassed by the monumental scale of a third phase which, as yet, has not been realized, but will consist of a life-sized section of a park.

Here is phase two, another model and it is a model for a section of a park in the shape of the filling, or rather the shape of the dental cavity after the filling fell out, in other words the negative of the filling. Like any cavity it is defined by what is not there and in a way that area of the park is defined as (a) nothing or, if you will, an absence. The small temporary cavity in her tooth has been transformed into a piece of land many times bigger than the artist herself.

Parks are by their very essence man-made structures, especially in the Netherlands where there is no unspoilt nature left. Our forests are parks, our parks are gardens and nature lives with us in our homes: more than any other people the Dutch decorate their houses with plants and flowers.

The thing about this park that distinguishes it from all other parks is that it’s not designed, not on the drawing board in any case. Its form originated randomly according to its own arbitrary (lack of) laws and in this respect it is closer to the rain forest than to the neat park where all kinds of functions for the public are taken into account. On the other hand, of course, it is designed after all, albeit originating from, and taking on the counter form of a random event; its defining moment was the artist’s decision to accept this event, this coincidence, as a constitutional moment in the genesis of an artwork. Coincidence is material in art. Had the filling never dropped from Nishiko’s tooth there would not have been an artwork at all and if it just came out without the artist paying it any more attention than going to the dentist to have a new filling put in its place, there wouldn’t have been an artwork either, just an event in daily life. To recap in slightly different words: what is being communicated to the viewer is the important fact that in principle any and every event in one’s life may or may not become an artwork, dependent on the artist’s say-so. In an even broader perspective each modest life event can grow to gargantuan proportions if the protagonist so decides – in the end it is all a matter of interpretation, of a lopsided way of looking at things, a constantly shifting way of experiencing and commenting on the world, in other words: being an artist.

If we consider the relationship between the artist and this work a bit more closely it can get quite complicated because of its constant movement. When Nishiko is walking in the park that is shaped after the cavity the filling left in her tooth, she is walking, as it were, inside her own mouth, or at least in a representation of it. Whether this is a concrete reality or not doesn’t make all that much difference, the same (idea of) movement remains: when we simplify it, it is just outside-inside. From there it is only a small step to the conclusion that Nishiko has turned herself inside out. In the first instance she has something in her mouth. In the second one she is physically present in the counter form outside herself; she lives, so to speak, inside her own tooth. And all the time she is both showing herself and taking the image back, she is constantly bouncing between her inside and her outside, a feat not many illusionists will be able to realize. And when she shows the work as a whole she invites us to join her in her endless dance between inside and outside, between form and its negation, thus becoming a human being in nature while also being nature in a human being, so to speak. The fact that in this way she welcomes us all into her body to tune in to this pagan dance-creation-ritual, rhythmically moving in and out may even be said to carry sexual overtones – in other words, we merge with the artist in an eternal, cosmic dance between turning inside out and vice versa. It’s like breathing – we all breathe as one entity being one with ‘nature’.

We live in our own bodies, so to speak, hardly aware of the age-old, essentially theological, dispute about whether we are our bodies or have them. Usually we just live there in our own bodies, those cylinders we call *I*, but we don’t externalize them – our body is ours and it is private and taken for granted. Like artists have done innumerable times before, Nishiko is showing us how our bodies are, or might be, related to the world at large, not only through spectacular events (the man on the moon, say) but also through small accidents that were initially meaningless; coincidences linking the big to the small, such as a dental filling to the cosmos if you like – everything is connected and part of the whole which, conversely, is an intellectual construct and Nishiko lifts a corner of the veil from an unexpected, modest angle.

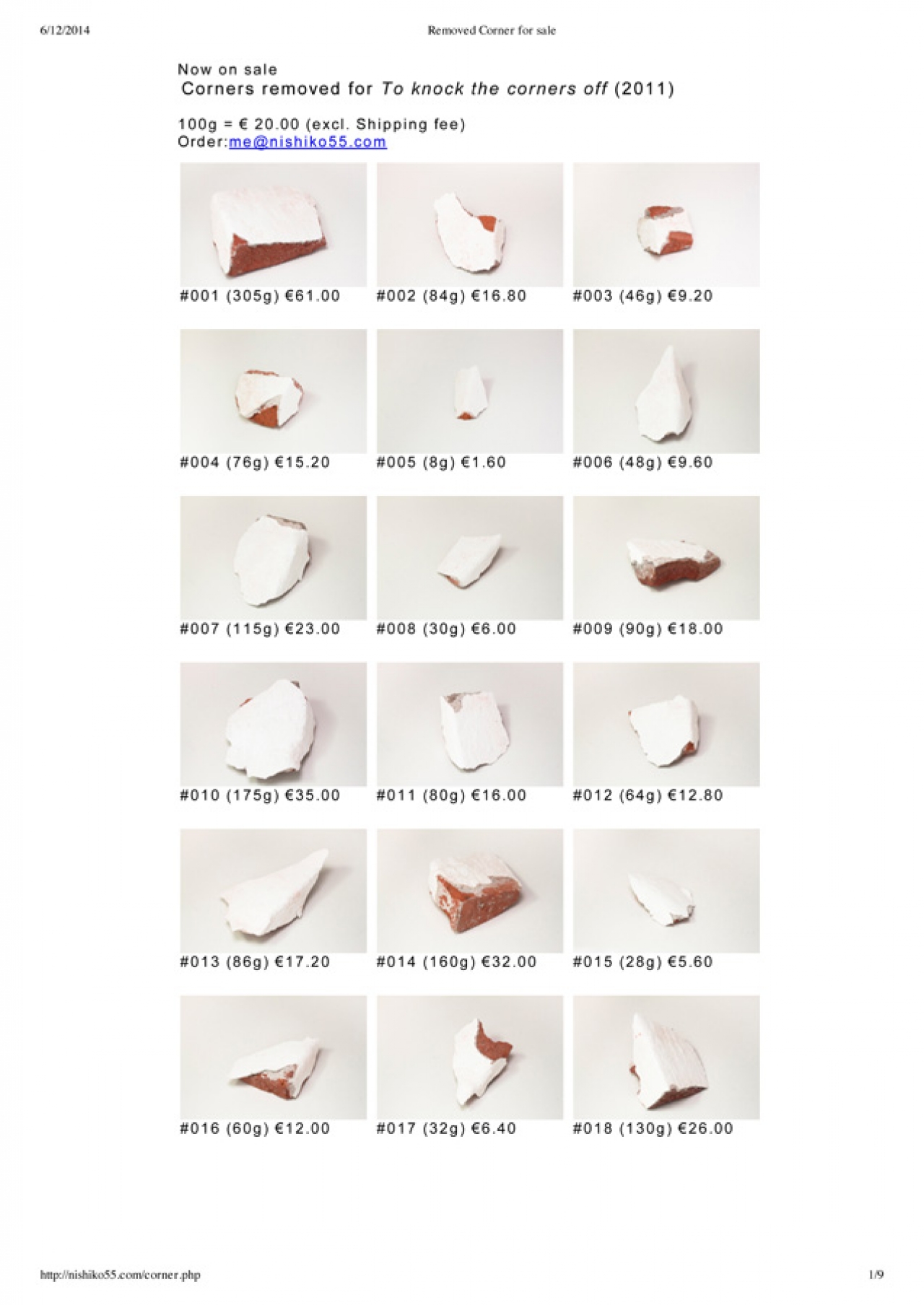

At some point it struck Nishiko that the word corner had negative connotations in many languages. Whether this is actually true in a significant way is debatable, to say the least, but that’s beside the point. The essential moment here is that, once again, Nishiko observed something almost completely meaningless in the world. She stumbled onto something small and totally unspectacular, something maybe no one else had ever noticed and which, partly because of these nondescript qualities, she could use to transform into an art project. In an effort to improve the world by getting rid of corners, Nishiko decided to remove all the corners from her studio which resulted in a cornerless space. So language transformed the visual appearance of the studio. But it wasn’t looking especially improved or more benevolent after the intervention. If anything, it ended up looking less finished. There may be something to say for working in an unfinished space, in the same way as the studio in the form of a backpack has its advantages. After all, when the artist sets out to make an artwork, it will also remain unfinished until the moment she stops working on it and even then one could argue that it isn’t finished because by definition it never is or can be. It is just a footstep on an almost imperceptible path of shifting sands, so to speak, an increasingly invisible trace of human presence. In this case once the corners were removed, the studio itself became the earliest incarnation of the work.

Of course there is a simple fallacy here, the fallacy of inversion. Language refers to something concrete and it is assumed that changing that concrete entity will result in a change for the better. Therefore, ideally, the negative opinions about corners will cease to exist once there are no corners left and the linguistic referral to them will become meaningless and, over time, might well vanish from the dictionary. This is a beautiful and also pathetic inversion based on the fact that language is experienced as literal while its true meaning, if any, lies in the realm of the metaphorical. It is not applicable to ‘real’ corners; the world won’t be changed if an artist somewhere removes the corners from her studio. At the same time, this attitude also implies a magical understanding of language and maybe even a delusion of grandeur (“I can change the world”). Mastery of language means power (“I’m so glad that no one knows that my name is Rumpelstiltskin” – knowing someone’s name gives you power over them, knowing that corners are bad gives you the power to do away with them).

But there is another way to look at this. If, just for the sake of argument, we maintain the idea that corners, meaning all the corners in the world, are ‘bad’, this would appear to be something we simply had to accept and live with, if only because of the scale of the problem. In this context, it becomes a very moving gesture that somewhere in this small country, the Netherlands, an artist is taking her responsibility and contributing silently to the well-being of the whole world, even if it only concerns a largely symbolic act. Then the work is about the little things we can do as opposed (or complementary, if you will) to, say, heroically dying on the battlefield. These little gestures are the hallmarks of true, peaceful civilization, vaguely comparable to monks all over the world praying for mankind every day and every night. Its very futility, the ‘power of the small’ (as the I Ching phrases it in a somewhat different context) is beautiful and touching and offers a hopeful view on the relationship between small and enormous, between private and public, between the personal and the global.

But there is more. Removing the corners of the studio meant that a lot of pieces of stone were left behind. These ‘corners’ are not recognizable as such anymore because they have been chiselled in different directions. As a matter of fact, they look like random pieces of stone that could have come from anywhere and may have served any purpose or none at all.

One way of presenting them is shown above where the price is determined by the weight of each piece. They look like archaeological artefacts that have no public use anymore, but would look nice on a mantelpiece, on a drawing room table or as part of an exhibition by a collector (Of what? Archaeological finds? Artworks? Arbitrary stones?). On the other hand, they don’t seem to be of much importance as they are not at all expensive. But maybe to the prospective buyer they are a real treat and they may or may not try to resell them at an astronomic price to an as yet unknown fellow lover of these kinds of stones, whatever they are and whatever defines their financial worth. For all we know, their prices may soar to unprecedented heights.

Knowing the background and provenance of the stones gives rise to a different problem: one could well maintain that selling the ‘corners’ is a way to spread evil. Or might the corners have lost their magic power now they are not corners in a space anymore but simply pieces of stone? Or is this maybe what the artist would have us believe and is she trying to sell us corners that are ‘artfully’ disguised as harmless stones? Is it a parody on the ‘real’ art market where artworks are primarily commodities no matter what their, other than financial, qualities are? To me such a stone would be a reference to Nishiko’s beautiful project, but in itself it would be nothing, so it would only have sentimental value and maybe the satisfactory feeling of taking part in this corner project. A questionable feeling that should be mistrusted because it feeds off a false desire to ‘belong’. And what would that sense of belonging mean to a small in-crowd of people who are in the know about this artwork as a whole, not unlike considerations that play a part in all other segments of ‘the art world’? This has nothing to do with art itself, although it incorporates all kinds of ‘art speak’, from the critical to the financial.

The first time I met her, Nishiko was still at art school. During the opening of a show which also included several other artists, she sat on the floor and was gluing broken glasses back together again. A very modest gesture speaking of loss and destruction as well as restoration, recycling and future; showing a precious love and respect for simple, everyday utensils, in keeping with an old Japanese custom translated into the art context.

While also making other artworks over the past years, Nishiko has been spending a lot of time working on a large-scale project called The Repairing Earthquake Project which focuses on the tsunami that hit Japan in 2011. More than 18,500 people were killed or went missing as a result of the tsunami and an innumerable number of others were, or are still, affected by the subsequent incident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

Since 2011, Nishiko has been travelling regularly to the region where the disaster took place – it had to be seen in order to be believed. She found simple utensils (like plates, saucers, cups and so on) that were broken and tried to find the missing pieces. Whenever she could retrieve these, she would glue them back together, and when she could not, she would add a monochromatic piece of ceramic in order to at least restore the object’s original form. Obviously in both cases the break lines remain visible – the objects were damaged and that shows. It goes without saying that the objects, in whatever state, all remain themselves. However, we can also see them as references to the people who used to handle them. That slightly changes the nomenclature: the subject is hurt, wounded, scarred, killed. Sometimes it can be healed, but the scars will always remain. There is no way to undo what has happened, but Nishiko’s gargantuan self-appointed task restores dignity and commemorates the historical events and the victims’ suffering. It shows love and compassion, even if, by and large, this is done through a symbolic gesture, a very small but beautiful and meaningful metaphor. I don’t know how many objects Nishiko has ‘saved’ in this way, but we are talking about a very large number. Each object is placed in a wonderfully simple wooden crate corresponding to the required size; all have received individual care according to their individual needs. The plates and the like may be exhibited in art presentations, and some have been, but they are not for sale as Nishiko stresses that they aren’t hers to sell, because she is not their owner. The people, dead or alive, who once used them are their true owners and nothing can change that. It seems worthwhile to reflect on this attitude, especially for people who believe that ownership is just a material category which can be expressed in terms of currency. On the other hand, there is no reason for the objects to be stored in a hiding place as they can also be seen and can even be preserved in someone’s house. A number of the works (the objects are all part of the larger project but they are also artworks in their own right, they are, so to speak, individuals) have found their way in the world according to Nishiko’s wishes: they are not property, they are on loan and in a secular way, to my mind, they are definitely images of devotion. The people who have one in their care, had to sign a statement to this purpose.

I am the custodian of one of the plates and I feel humbled and honoured by being involved in this small way with both the victims of the tsunami and with Nishiko’s loving care towards people and things. It has been a learning experience.

There are many more aspects to the Repairing Earthquake Project that I will not go into at this point, while the work is still developing. Moreover, the website of Nishiko documents all of the work and may be seen as part of the art project itself.