Straight from the archives

An interview with Jean-Gabriel Périot

We could say that Jean-Gabriel Périot is the French king of archive cinema – many of the 17 short films he made since 2002 are made with pre-existing footage. Almost all his films are successful at film festivals, but we can’t say that he keeps repeating the same trick: Périot keeps using different forms and narratives to tell his story. There are certain themes that keep popping up in his work though: violence, politics and war for example.

Mister Motley took some of the ending shots of his ‘archive films’ and asked Périot what his thoughts were when he first encountered these images.

Jean-Gabriel Périot: I knew this excerpt before I started making “The Devil” because it was used in one of my favorite films by Santiago Alvarez – an amazing Cuban filmmaker from the 1960’s. The speech, where this still is taken from, is in itself really powerful, particularly in the end when “we are beautiful” is repeated. At that moment in my life I needed to do a film with a strong political appeal, so when I started to edit this film there was no choice but to end the film with this footage.

Mister Motley: Do you use video material from the past to express political views or dilemma’s that are going on in the present?

JGP: History never repeats itself, but politics could. Politics are about power and people fighting for that power – this has been a part of our society in the past, in the present and this fight will probably go on forever. So to question what violence was or what war was, is questioning what violence is and what war is. Showing images of people who struggled and who fought against destruction for a better world is a way to show that it was possible then, and therefore it should be possible today.

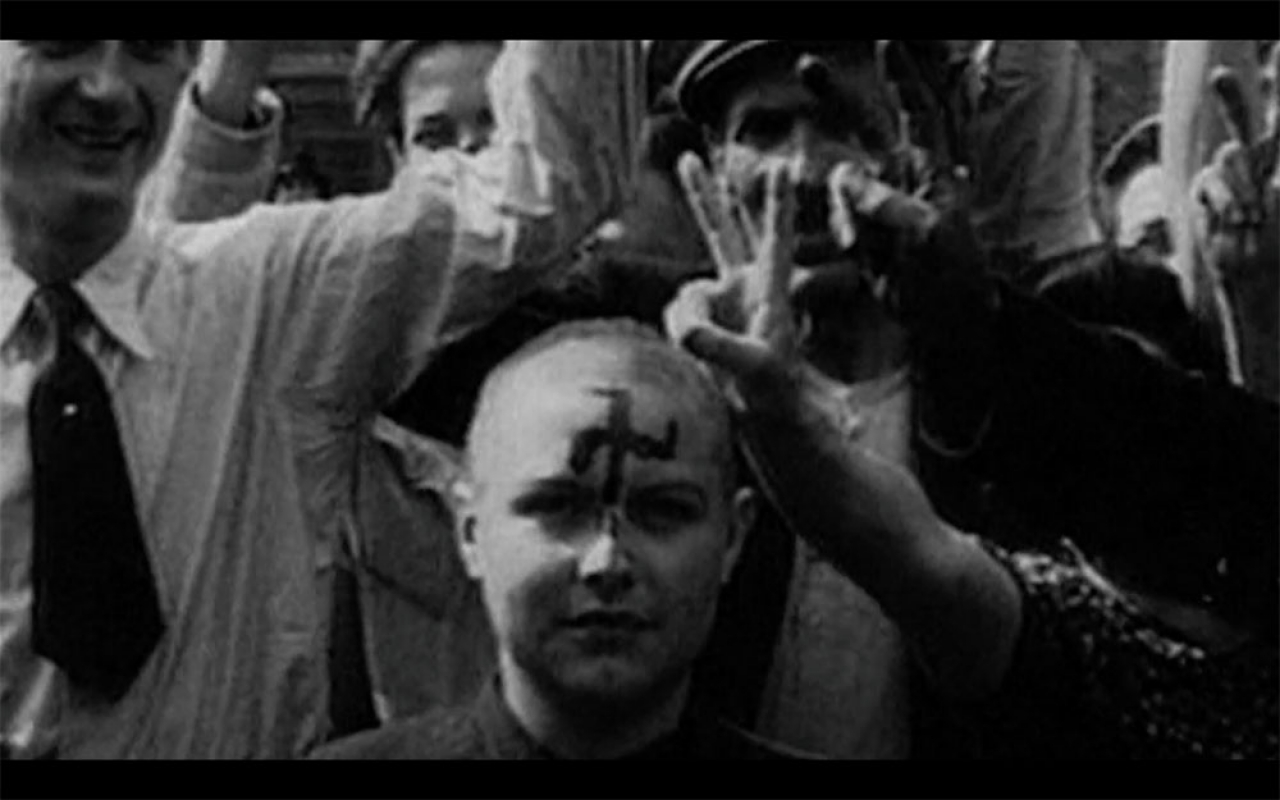

Watch Even If She Had Been a Criminal…

JGP: I stumbled upon this footage of the public shaving of French women who were accused of being collaborators when I was working on a video installation about images of war. I was really shocked by them. Some might see them as less painful than other images from the same period (like the videos of the liberation of concentration camps), but I found them really hurting. When I watched them for the first time, I only saw the women themselves. Only while editing the footage for the installation, I slowly started to notice what was happening around the women. When I discovered the people participating in this public humiliation and enjoying it, the footage became even more disgusting. That was when I realized I needed to make a film with this footage.

MM: In which direction do you usually work: do you search for the right archive images to express a thought or raise a certain question, or do you get your ideas for films by simply watching a lot of archive material?

JGP: It is both! Usually, I find a topic and decide to build a film around it. Then I start researching, and the first pictures or footage I find, help me focus and specify the questions I want to raise and the form the film should have. From that point, I’ll continue the process of researching, finding new material, editing, and so on.

“Even if she had been a Criminal…” is the only exception. I saw the footage and I was hurt by it. I needed to make a film with those images. It is my only film that came straight from the archives themselves.

MM: What do the images in ‘Even if she had been a Criminal…’ tell us about questions or problems we face nowadays?

JGP: You can look at the film as a representation of the historical event of shaving women in France after the war, but you can also see it as a film that questions us about the way we still hurt the powerless people today. And not only women, but all people who are too fragile and too weak to be able to defend themselves. The film also deals with questions about revenge and justice that are still burning today.

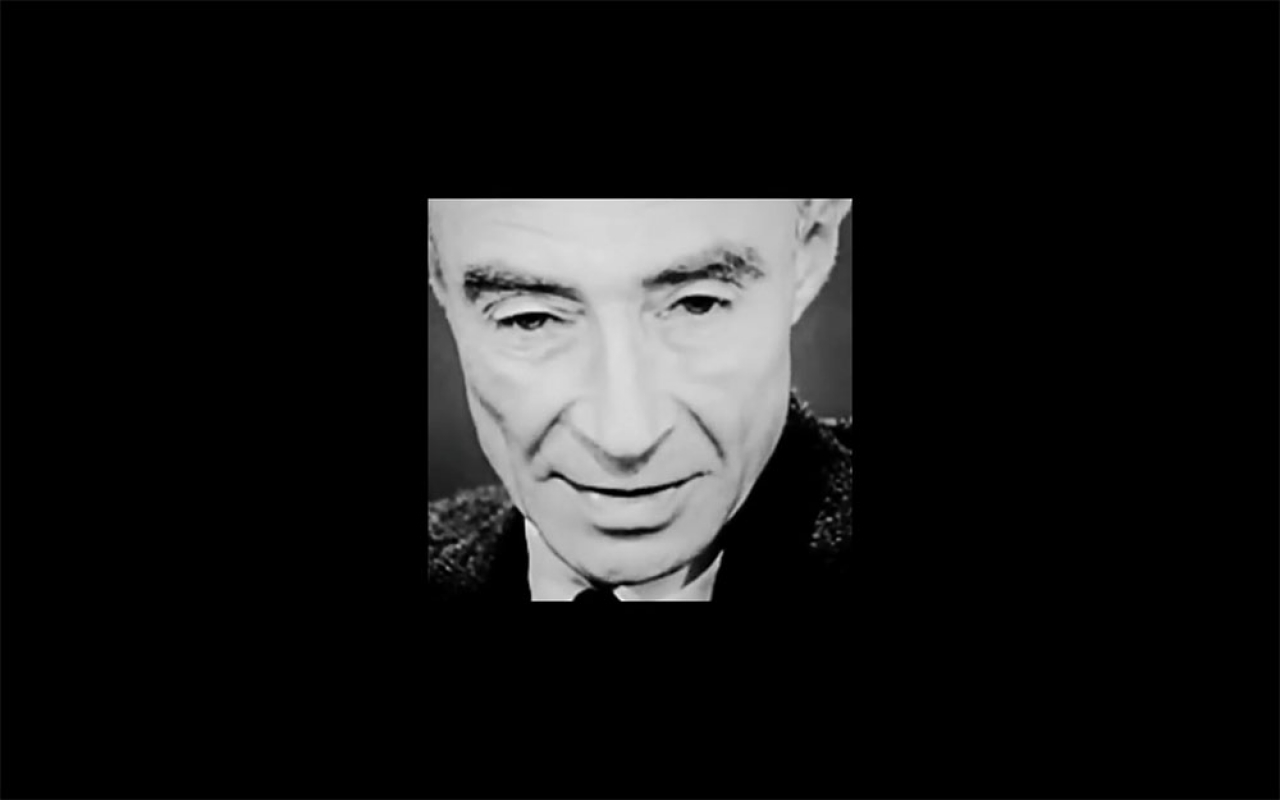

JGP: This footage is quite famous as Oppenheimer appears really strange in it, almost like a ghost. The atomic bomb killed thousands of people and could still destroy the world. Oppenheimer, often called one of the fathers of the atomic bomb, could regret endlessly, but it was already too late when he did this interview… and he knew it. There is something really human in this footage, about how stupid we can be!

MM: You look at this footage as material with a historical context. Do you also use images out of context and more as autonomous material – for as far as possible?

JGP: In an archive film we can discover how a filmmaker sees preexisting images. It is more about showing how images could be seen by someone’s eyes, with his own sensibility and his own mind, than to just bring back some images that were lost or unknown or to put a new light on some past events. Like I explained earlier: filmmakers see those images with contemporary eyes, and not as someone who saw them at the time. There is always a visual translation.

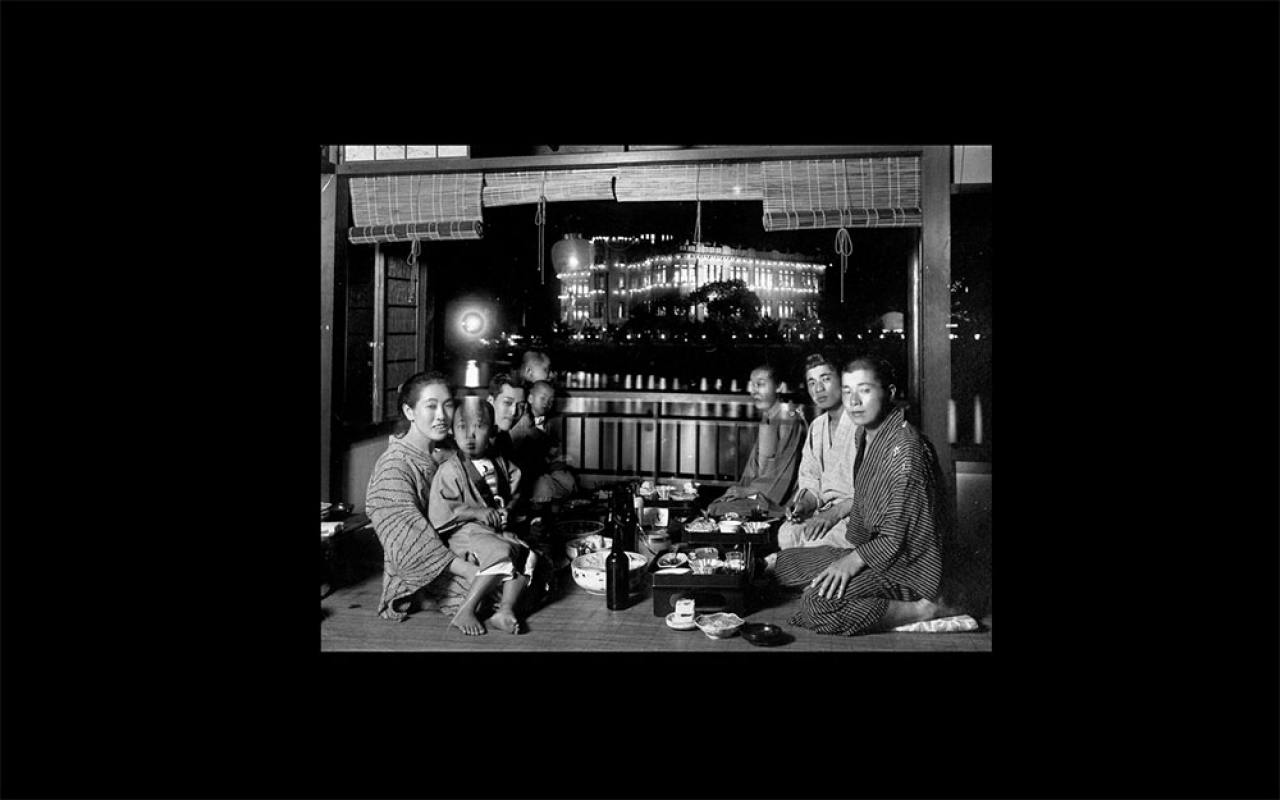

JGP: I watched tons of pictures in my research for this film and this one came really unexpected. At that time, it was difficult to shoot such a portrait outside of a studio at night; photographers needed a longer camera exposure time. As some of the people in the picture moved, they eventually appeared as ghosts in the image.

I couldn’t use this picture because I wanted it to appear in the first part of the film, but that was impossible because of the strange framing. The picture became really important for me though, so I decided to create some space for it at the end of the film. By doing so, I also created some kind of loop: we go back to the beginning of the film, and moreover, it brings back humans (and ghosts) in the film that at that point became quite abstract.

MM: What makes this picture so powerful?

JGP: For me, it is really important to try to know everything about the images I use; when and where they were made, by whom, and for what purpose. It helps to read and understand them. But, on other hand, it is also really important to keep my own sensibility when I face the images. Some move me more than others, raise more questions or seem more complex – it is important to stay on that level too. Despite all the knowledge you have about an image, in the end they always remain unclear. And there, in this darkness, the precise power of an image is hidden.

Watch We Are Winning Don’t Forget

JGP: I found two really strange pictures when I was looking for footage of demonstrations and riots for “We Are Winning Don’t Forget”. This one, and one that represents a wall with the inscription “We are winning don’t forget”, which I finally used as title. Just like with the last picture of “Nijuman no borei”, I needed to find a space for this one. I still don’t really know why, but for me this image is full of hope. As I didn’t want to end the film with a dead demonstrator, I used this picture to open up the film.

MM: How is your hope for the future of archives: with smart phones and platforms as youtube we are creating a new visual history for ourselves – any thoughts on how this will change the way we will look back in the future on this period?

JGP: I simply have no idea! I’m sure that a large part of this memory will be erased, like all human productions were always lost in numbers. People and also companies and states take care of their own archives badly. They often don’t copy and save their own material. So, obviously, and fortunately, this amazing amount of mostly poor material will disappear.

But I think that in many years, when people will watch back on our times, they will probably see us as egocentric humans wasting their time to document their own life and making images about nothing!