MASTER OF LIQUID DEVICES: Hito Steyerl

During the most recent edition of the Berlin Art-Week, the video and performance artist Hito Steyerl had a retrospective of her most recent video-art installations, showing at the KOW institute’s gallery in the incredibly hip Brunnenstrasse.

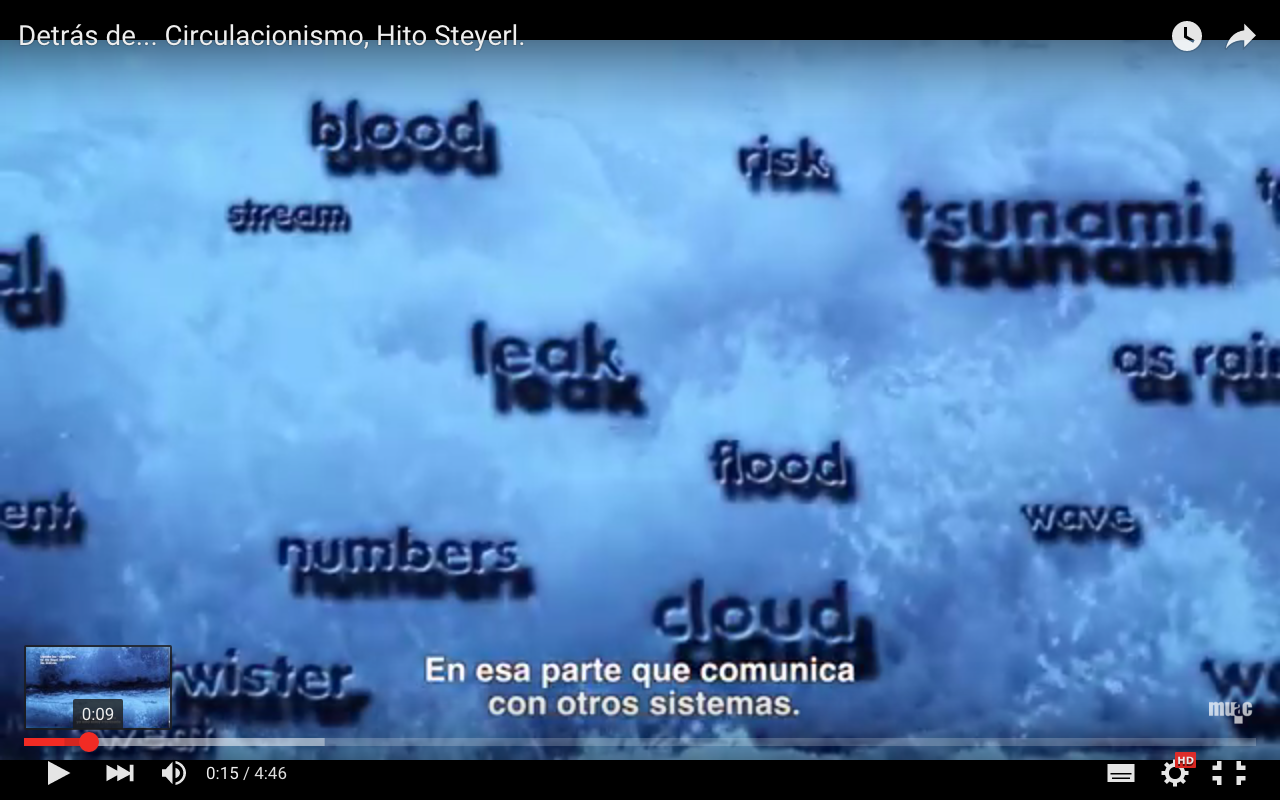

The theme for the show, as repeated by Kow’s publicity, was the echoing of Bruce Lee’s command ”Be Water, my Friend!” Much of Steyerl’s work deals with ”liquidity”, or the way in which societies and individuals become liquefied, without steady form or substance, in a world of financial instability and violent spectacular changes.

Hito Steyerl studied “movement of art and image” in her maternal Japan, before earning a philosophy doctorate at Vienna University. Despite her theoretical framework, it seems the education in moving images has defined and influenced her art, far more than the philosophy which is the stuff of her prefaces, her explanations and ornamentations to her art. But in an art-world wherein theoretical framework is appraised as superior to the object of art, the decorative philosophy is presented by Steyerl with the excellent craft of both painter and actress. The artist’s chosen fixation with the concept of ”liquidity” brings to mind a hint at the work of philosopher and sociologist Zygmunt Bauman. ”Liquid modernity” is Bauman’s term for the postmodern cultural logic, in which all social relations and certainties of societies and of individuals are liquefied and made uncertain in a world where William Butler Yeats’ vision of ”the centre cannot hold” becomes everyday reality.

Hito Steyerl rises above German video artists and is a professor of New Media Art at the Berlin art academy. The video art-works are meticulous in craft and presentation. At times, the azure waves and the cinematographic projection are dizzying and provide a sense of adventure and of ”interactivity”. It seems quite clear that Steyerl aims for a young audience: a video-game-like presentation seems to goad them into thinking they, the viewers, are in control.

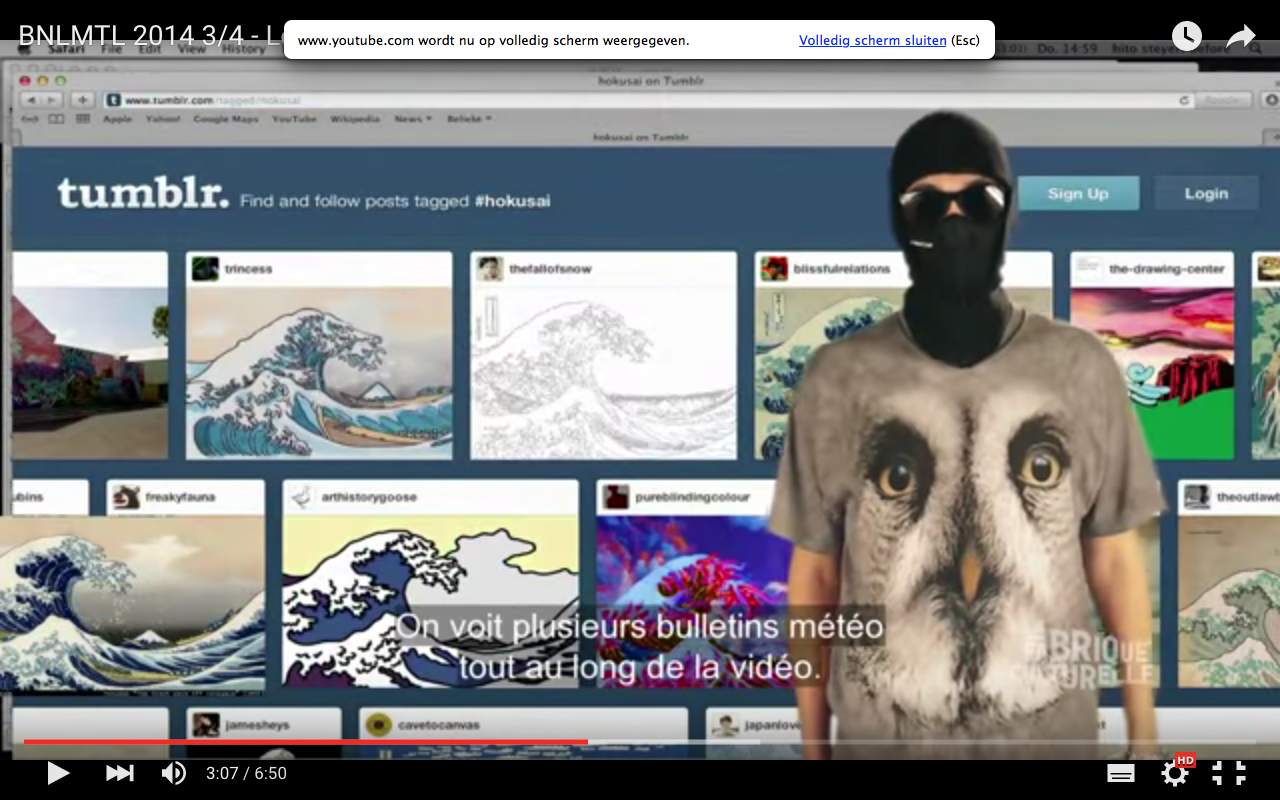

Liquidity Inc often quotes the Japanese art of Hokusai and Hiroshige, (who are among the milestones of drawing art studied in the animation academies of Japan) The film possesses the same violence, the blitz of colours that almost sear and paralyze, and all the comic antics and neurotic aggression of a manga or anime. The violence of the video-game is interspersed with film footage of the bloody martial arts tournament for MMA (mixed martial arts) fighters, called Ultimate Fighting Championship. Despite being a very real and physical endeavor, the Ultimate Fighting Championship itself comes to resemble the video-game, just as imitated video-games about martial arts often imitated the UFC tournament that thrived financially thanks to video-rentals and the investment from the video game industry’s investment. The tournament makes garish entertainment of desperate fighters and would-be mercenaries, who seem to embody the kind of ultimate freedom promised by the economy, despite that their fates are controlled by adverse interests and onlookers.

Art that is used in Anime and manga is seemingly futuristic, though it relies on Japanese traditions of drawing and of sketching the semblance of movement (already to be seen in the flight of Hiroshige’s birds, clouds and waves he painted on breath-taking woodcuts) Today these traditions culminate in very violent, consumptive forms: the computer game, the anime film, the ”manga” comic, all existing between total neurotic aggression and paralysis, in which the typical consumer of that form can recognize their lives of conformity, work, frustration and pleasure as if the citizen were gazing into a ridiculing mirror. These art forms, like many contemporary forms, have advanced a formal anti-poetry, reinforcing the viewers’ comfort in alienation, never disquieting them unto a reality that undoes the estrangement, as the arcade aesthetic narrows the consumer’s mind and defines his lot for him rather than liberating. Perhaps, hopefully, films like Steyerl’s might evolve one day into an actual subversion of such art-for-liquid-death and might derail the assembly line. Liquidity Inc. has the feel and flavour of the first in a trilogy, and it promises that Steyerl’s oeuvre aims towards the subversion in future episodes. Beyond any doubt this noisy, exhausting yet tantalizing video-art piece is the best work by Steyerl on exhibition at the KOW in Germany.

The non-narrative movie, actually a long piece of video art, seeks to illustrate the internal monologues and adventures of the real-life Jacob Wood, who was a war-orphan born in Vietnam and who became a clerk and investment banker of the Lehman Brothers’ firm. After the 2008 crisis Wood went into a martial arts career and joined the Ultimate Fighting Championship tournaments. However, the film does nothing to characterize Wood’s life or personality, in a way that a novel or a documentary would do for this very interesting character. Steyerl has made a video-art piece inspired by this character in the way that a painter makes a portrait inspired by a personality they have encountered in life or literature.

Without reading the fine print or the back-story presented on the exhibition flyers, Liquidity Inc. seems to be a succession of images that attempt to say something about capitalism, dehumanization and excess. The computer generated sea expands, refugees drown, and online chats appear like sharks. In the chats, massive amounts of money and exports are discussed by young businessmen.

The soullessness of an increasingly flat, liquid world is well-captured by Steyerl. The images of water, implicating a flood coming to engulf humanity but without any hope for a Noah’s ark, are interspersed with weather forecasts by a man in a ski-mask who looks as if he is about to be beheaded in an ISIS video and is quite enthusiastically looking forward to it. The scenes from the famous “Ultimate Fighting Championship” for MMA, Mixed Martial Arts fighters, show kick-boxers fight in a cage, surrounded by bikini-girls and a roaring audience rooting for their favorite gladiators. Their beating at each other seems to have liquidation as the intent.

The drowned, bubbly bodies caught by drip-nets, imply Steyerl recently added the Syrian/Eritrean refugee crisis to the mix, in response to the supervised drownings in the Mediterranean. The drowned corpses are comically rendered with Computer Graphics as well. Rather than create meaning, its absence is exhibited and criticized with tongue-in-cheek, as goes the formulaic ideology behind most contemporary art.

Steyerl’s is a work of irony, and in that aesthetic objective of irony not at all exceptional among contemporary art that sees Irony as the highest possible subversion, when it is in fact the lowest. In the virtual reality vault she sets up, the viewer becomes the subject of the drained and emptied video world, while able to lounge on bean-chairs and be entertained, coolly, by the cynically exposed truth, as it is a world of Leviathan that accepts its diluvian fate. Potato chips and beer go down well with the experience. Here the problem is not so much the lack of redemption, as redemption itself is perhaps too moralistic to the point of idiocy—and Steyerl is a moralist, as her films like Is the Museum a Battlefield? confirm. More troubling is her total absence of any resistance to the soulless engine—there is no poetic resistance to alienation, only tongue-in-cheek commentary, sulking and snickering, all while we embrace it. We are given the planet of cruelty as if it is a balloon to be held. In that sense Steyerl’s art is innately within the scope of official contemporary art, of an art establishment that exalts its own level of social awareness. This art-world radicalism and vanguardism is the exact reverse of Gramsci’s hope for the radicals to come: the prison philosopher, and theoretical companion to Pasolini, Antonio Gramsci had believed in the radical intellectual being ” a pessimist of the intellect and an optimist of the will” The art world’s radicalism is that of being either deeply pessimists-of-the-will or optimists of the intellect, never noticing that these two poles actually go together, un-contradictory and unarmed by any internal conflict. Such art glows, radiant in its absolute coolness, after the catharsis of any conflicting forces has long since been resolved, like the nuclear winter over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Hito Steyerl shows us the dehumanization, yes. But Hito also does nothing to prevent enjoyment of witnessing the dehumanization-spectacle. The only friction, then, between being in the audience of the Steyerl film or being in the audience of Ultimate Fighting Championship is the preservation of taste and class: the mostly younger and educated audience of the Steyerl film need not mix with the desperate, lonely and inarticulate people, those who will cheer the Ultimate Fighting gladiators and admire the bikini girls circling the ring.

One room at the Berlin gallery screened her film Guards, produced at the Art Institute of Chicago. According to the description on Steyerl’s page on artistspaces.org, the Guards “centers on conversations with museum security staff with previous military or law enforcement careers. Their descriptions of tactics and strategy point to the museum as a site of militarization and privatization, and to their contradictory position between visibility and invisibility within a space of pure affect and sensation.” The film attempts to prove once again Steyerl’s obsession: the Museum as hell. Even if the museum spotlights her, the Museum is the core of her hell.

The official, parental and stately Museum, which she is quite at home in or in any case has never shied from exhibiting in (as she did in 2014 at the Stedelijk Museum of the Netherlands for example) constitutes a ”battlefield” that uses art to curtain the forces of violence and vested power interests.

Looking at Guards, blindly, without the captions, gave me a different idea as to her intentions and enabled me to see and appreciate the film for precisely what it cannot be, and what it did not intend to be: accidentally warm, humane portraits lining up the museum security guards, who are eager to finally be the center of attention rather than a shadow or a silent backdrop not unlike the security cameras. All of the guards have distinct personalities, and the typical training that is expected of any security guard whether he works at a nightclub, at a museum or at McDonalds (past military, security or police experience, perhaps having done watch-duty at a prison; at least one black belt in a martial art and fighting experience.) All of them are black men who at some point went into the army. They are eager to show their martial arts moves. Anyone who ever took classes in martial arts has met champion fighters who lead the un-glamorous professions of working shifts as security guards, often in nightclubs, prisons and museums but also in less flamboyant locations. Martial arts have tended to be popular among young men in poorer parts of society, young men who get into a lot of fights at school and elsewhere and who watched action films. Martial arts schools or ”dojos” are typically implemented and supported by community centers in poor areas as an attempt to help young people off drugs, to learn discipline, to channel aggression.

In the theoretical contextualization she gives to these guards, Steyerl tries to make them seem unique to the ”Museum world,” and their violence a ”revelation.” It is surprising she only know notices that the guards at prestigious museums can seem ominous in their suspicion and boredom.

If the security guard at McDonalds, at a typical nightclub or at nearly any other cultural institute that hires security personnel were asked, instantly he would show off his martial arts CV and give a demonstration. Perhaps Steyerl succeeds here, but only by accident, as her only target of exploration and of habitation is the Museum. By accident, Guards opens a door to understanding far more interesting contexts than the hellish Museum where she exhibits (such as in the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam in 2014). The experiment also reinforces that not only museums, but also the nightclub world, the high school world, fast food eateries, parking lots and shopping arcades are all places of high intensity aggression and violence, just like maximum security prisons. Places of consumption have even more police and security regime presence, and are far more violent than the Museum, unless we take into account the vulture-like violence of the hordes of tourists (not only or specifically Japanese) flicking their cameras at every Venus as if they will instantly forget it without the aid.

A complementary installation at Left to Our Own devices, intended to make sure we return to Steyerl’s favourite question and preferred nemesis, bears the title

IS THE MUSEUM A BATTLEFIELD?

Steyerl’s third installation at the Berlin gallery is the 2013 movie Is the Museum a Battlefield? once again attempts at furthering her thesis: the Museum is not just a state-maintained building with rooms covered in art; it is a place of warfare and violence.

The artist appears in the video making mime-like motions with her hands, speaking somewhat as if in the impersonation of a robot from a sci-fi film, perhaps the adequate tone for such commonplace art-world discourse and official wisdom about how art must be about “the circumstances of production”.

In the video about the Syrian war, Hito Steyerl attempts to incriminate the art world with its involvement in the Assad regime, by pointing out to how an architecture star like Rem Koolhaas among other European museum-world officials were helping to design the infrastructure for a museum in Syria while cooperating with Assad’s ministry of culture. Such strange use of museums to consolidate pacts in international relations and diplomacy happens more often.

Yet Steyerl’s attempt to un-curtain the imperialism or corruption behind the museums is a playful one and instead serves to reinforce the imperial idea: it seems to argue that the West and its museums should only cooperate with democratic governments, rather than engaging with an enemy towards achieving a goal that might benefit the people ruled by the enemy regime. That the museum was entirely ineffective in bargaining or resolving military and international disputes is clear from the withdrawal of the project from Syria when hostilities escalated: it disproves the current, prevailing official wisdom of art was a tool for doing political activist diplomacy, art’s function as being a platform for advancing democracy has failed drastically and will continue to fail, with one spectacle after another. The love and passions that inhabit humans are not the cordons that make pacts between states or corporations. But Steyerl is another art-politician, again demanding a diplomatic utility for art in a mass democracy, despite that these aesthetics are primarily expressed by the most hegemonic and hierarchical levels of the art establishment, whereas a Nietzschean disgruntled idea is more common among the artists who are unable to pay the rent and have not past the gatekeepers.

Regardless of the government that rules it, Syria is the home of ancient archeological sites and art, and was the homeland of many artists who might have wanted to leave Syria for a career in the West even before the war. A question unexplored by Steyerl (as it is impossible to explore in any art piece, unless there is a newspaper item used in a collage) is whether cooperation between Western museums and the Baath regime’s ministry culture might have led to better preservation of Syria’s heritage, currently under attack. In all likelihood, UNESCO World Heritage might have contributed to the preservation of Petra and other ancient sites, despite the Jordanian police state and royal regime. Such preservation is necessary in a time of right wing religious party’s vandalism and when even the Saudi Kingdom will gladly bulldoze the sites surrounding Mecca and Medina where the prophets of Islam had lived and taught. The museum plans that would have kept this treasure inside Syria, were of course derailed by a war that has not improved Syrian hopes for democracy or transformation. No Museum could have resisted the bombings, but no museum is complicit in them either. If the plans between the West’s and the Assad government’s museum officials were somehow corrupt or violent, is it less violent for the ancient objects to be shipped from Syria and from Iraq when they are endangered, when these countries come under attack and their fleeing populations are denied safe harbor? Perhaps in that contradiction, Steyerl’s belief in violence underlying the museum world still holds ground: the artifacts and pieces of ancient sites like Palmyra in Syria and Iraq are welcome to be transferred for safekeeping in the Louvre and British Museum, and are perhaps even being smuggled by the invading mercenaries of the Islamic State movement. But the Syrians and Iraqis who continuously inhabited ancient cities like Aleppo and Kirkuk, knowing their secrets and keeping them intact, are far less welcome in the European Union when they have to flee a war. Museums certainly play a major role in diplomacy, as in the exhibitions of Iranian art that took place despite Cameron’s and other conservatives’ bickering against a nuclear deal with Iran.

A role of demonstrating power through art is not new; for example, the Vatican made much use of powerful art during and centuries after the Middle Ages to enforce and illuminate its negotiations.

In her performance as robot-cyborg-philosopher, the academic Steyerl presents without any satire the view that she and her contemporaries adhere to: rather than an intimate mirror or world of the artist, or an attempt to see the reality that exists wildly far away from museum spaces, art and artists must turn inwards, towards a kind of moralist introspection, a grieving imperial inward search. Steyerl embraces the unarguable official wisdom, that Art and artists must comment, with much irony and tongue-in-cheek but also with solemnity, on the residencies they are accepted to around the world, and upon the awkwardness of their fortune to be in a position to make and exhibit art.

Such ”awareness” of the ”circumstances of production” implies a commentary, but not on reality—for reality is supposedly inaccessible, or at best only accessible to people in the empirical professions such as economists, social scientists and so forth. Instead, the artist must comment on the museum spaces that give the star her established voice and platform, and on the innate irrelevance of art altogether, in a world where there exists this mysterious force called Oppression: so goes the cultural logic, the current mood of the art establishment and its ranks of ambitious coordinators (called ”curators”).

Steyerl’s model exhibits of small jetplanes cast their shadows over a model desert she made. The airplanes and desert are the interesting centerpiece, contrasting with her intellectual sermon.

Surely there is much to her argument: today’s intellectuals of the Left have had to defend Karl Marx’s decision to study at the British Museum while conducting his research, despite that the British Museum was an accomplishment of the zenith of imperial and colonial advancement, containing the studies and objects that were taken from Asia and Africa during the plunder and rape of the colonies. But Marx was too committed and serious an intellectual. He refused to be moralistic or to boycott an institute such as the British Museum Library where he could enrich his mind and studies with the accumulated, immense reservoirs of knowledge there present for any library-card-holder. The linguist and leftist activist-scholar Noam Chomsky, in recent years has often been charged and called out by activists for his professorship at MIT, also gives the example of Karl Marx’s difficult decision. Despite Chomsky’s life-long struggle to expose and critique imperialism and the industries of war, he has to contend with the reality of valuing that freedom granted to him by his tenure at MIT, which contains the laboratories for Lockheed Martin’s and Boeing’s weapons research down the aisle from his office. By keeping close to the intellectual center and nexus that learns from the war-industry, Chomsky keeps his penetrating and scathing social awareness and perceptions. It is doubtful that Hito Steyerl could accept such compromise. She instead opts for moralism, and the facile irony of pointing out that artists perform in museums that will, inevitably, depend on funding from the corrupt centers of power.