Exploring Serbia’s history through art

Photo: Tomas van der Heijden

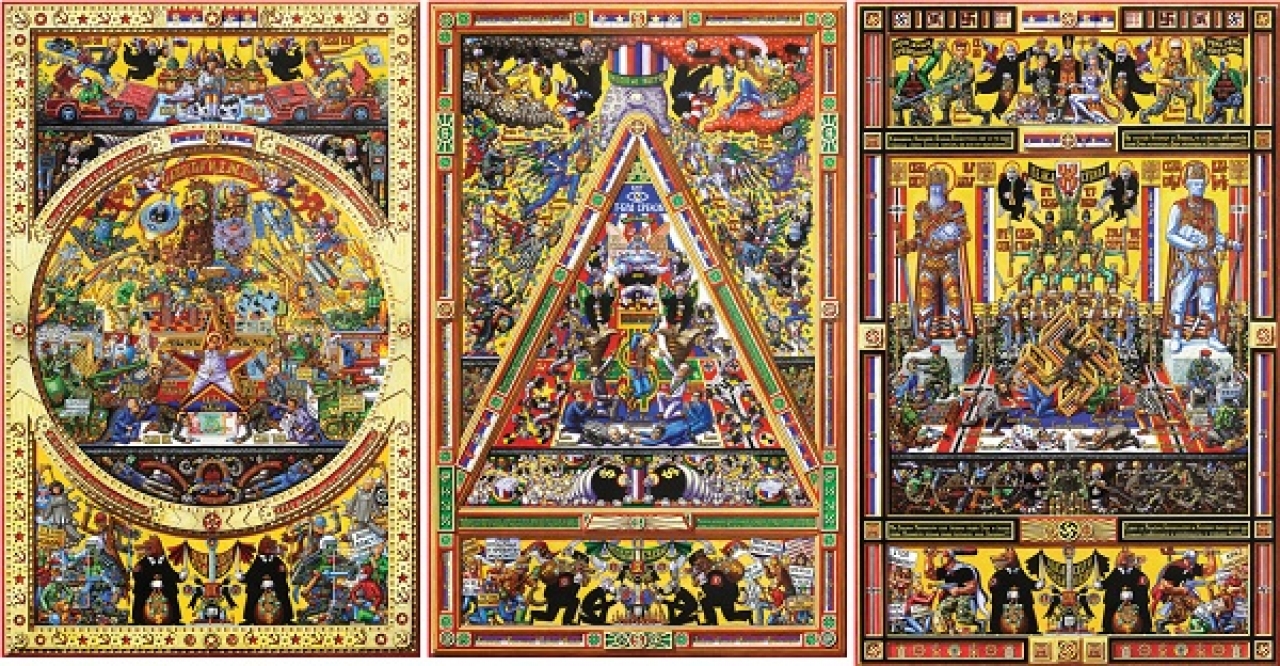

Serbia as the prey of three different ideologies can be seen as the main message in the latest work of Belgrade artist Aleksandar Todorovic, who expresses through his incredibly detailed paintings the pessimistic scenarios for Serbian youngsters.

A young girl walks by the paintings, steps toward them, squints her eyes and laughs. Painting by painting she acts surprised, shocked and then amused. “I constantly recognise my country in many, many ways. But let’s say that it is better to laugh than to cry about the history.”

Laughing and crying is what best summarises the latest collection of Aleksandar Todorovic (33), who is on Thames & Hudson’s list of the 100 most promising artists worldwide. His work is full of symbolism such as flags, priests, absurdities and leaders of the old country. All in hard and clear colours that are carefully applied with a miniature brush.

In every painting the centre is occupied by a crucified man, nailed on the symbol of his own ideals. Communist president Josip Tito hangs on a socialist star, Milos ‘Knez’ Obrenovic (old monarch) rests on a dollar and old general Draža Mihailović is attached to a swastika carried by war-criminals of the 90s. The space around the leaders is filled with threats such as incoming tanks, bombs or money. In the case of the ‘Socialism’ painting, fat men with money slash their axes into the heads of Marx and Engels, the founding fathers of communism, in order to represent how money dismissed the original idea of equality.

What is clever about the different paintings is how Aleks manages to portray ideology not only by symbols but in many other ways by using texts, shapes and lines. The first painting is predominantly round and every line seems to be part of a circle, which reminds the viewer of equality and harmony. Capitalism (or Americanism) centers on blue and green to represent liberalism and money, the triangle frame underlines the hierarchy in western society that is – in the eyes of Aleks – based on money. America’s tagline ‘In God we trust’ is strikingly replaced with ‘In Gold we trust’ and we see men in suits striving for the top in order to reach the gold. Fascism on the other hand is mainly black, firm and strict: lines are hard, concrete and square.

The three paintings are the herald of a bigger, and more complex, work that is not directly an ideology but the blend of the first three. It is Serbia. This time there is no leader crucified but a poor Serbian peasant. He hangs on a Swastika that rests on socialistic stars and dollar signs. Around him, fat ‘leaders’ run with money in the one hand and flags of Europe, Russia or America in the other.

Is it possible at all to deconstruct Serbia on the basis of three ideologies?

“Things are never black and white and I don’t want to pretend that Serbia has been one of these ideologies for the full 100 percent. If you take a careful look into the paintings you will see a lot of old leaders featuring in the different paintings. Our old nationalistic leader Slobodan Milošević [who had to face international courts for his war crimes during the 90s], for example, appears in the socialism painting when he admires Tito, while in the capitalism painting he is handcuffed and in the fascism painting he writes a contract on his knees while he bends over gold. To summarise: while pointing to socialism and being trapped by capitalism he is a true nationalist. The paintings constantly interfere with each other because our leaders switch and shop constantly between different ideas.”

Your use of swastikas is striking and can be offensive, why do you use them so much?

“Serbia wasn’t of course a part of Nazism but it had to deal with a lot of nationalism which reminds people of fascism. The swastika is a Nazi-symbol and at the same time the most terrible result of strong nationalism. That’s why I ‘borrow’ it. I want to stress the danger of this ideology.”

Are you a pessimist or just a realist?

“I am part of a war generation and have seen my country fall apart several times. Being an optimist is hard. Younger Serbs who didn’t experience the war directly are often more optimistic.”

Hover over the painting to discover Serbian history and statements of Aleksandar Todorovic.

Todorovic’s exhibition in the Stab-gallery in Belgrade is over now but his work will be shown again on the 18th of September in Art Brute and Art Singulaire in Paris.