The curatorial ego is dangerous – in conversation with Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

For her last interview in this series, Rita Ouédraogo spoke with Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide. Van der Heide is exhibition curator at Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Her interests lie in diverse intersecting perspectives – institutional, trans-local, feminist, queer, intersectional, and modes that decentre the oppressor in practices of freedom and liberation – to influence art institutional practices. ‘Museum gallery spaces, white cube spaces have so much authority, but it’s all constructed and made by people. So we can shift and change it when it doesn’t serve us.’

In the past years I have been in conversation with artists, thinkers, makers, breakers, curators, organizers and writers for the series ‘Hoe hoog zijn de muren’. An interviewseries through which I aim to explore the ‘walls’ of the art/cultural-world we work in. By being in open conversation with inspiring people I hoped to gain more insight in the practice and strategies people make use of in order to navigate, uphold and enjoy the work they do.

For the last conversation in this series, I had the pleasure of speaking with Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide. Van der Heide is exhibition curator at Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Her interests lie in diverse intersecting perspectives – institutional, trans-local, feminist, queer, intersectional, and modes that decentre the oppressor in practices of freedom and liberation – to influence art institutional practices. Previously she worked as deputy director at Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons, where she started as an intern in 2008.

Do you see yourself working at institutions for a long time?

Whether I like to admit it or not, I think it’s in my DNA somehow. I worked at Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons, in Utrecht for a decade where I witnessed and contributed to Casco’s shift in scale, transforming from operating out of a storefront-like or one-gallery space like Buro Stedelijk to midscale institution, conscientious of catching up to it’s programming or practicing what was preached in the public program. All this is to say that your processed-based working style at Buro resembles how I grew up and resonates with the legacy of Casco, which began in the early ’90s as an artist-run space that gradually institutionalized with directorships by Lisette Smits, Emily Pethick and Binna Choi, whom I worked under. There is still some of this process-based sensibility living in me and is how I tend to operate at the Van Abbemuseum, where I work as Senior Curator.

Casco seems like an institution that is not that ‘institutional’, but perhaps, that doesn’t exist. By this I mean the structures, the system that ask of you to be hyper-vigilant, to be hyper-aware because if you are not, you will be absorbed by it. With these big institutions you come in with a certain awareness that will at least prepare you a little bit. Then with smaller institutions, that seem ‘radical’, you often have to deal with the fact that they are not that ‘radical’. You can’t outsmart the system or the institution. I think you might be more aware of these systems when you are working for a big institution that can never even act as if it’s not one. Were there certain strategies you had to learn?

Yes, I would agree. I think Utrecht is quite a specific city with a huge demographic of young people, something like one in four Utrechters is between 20 and 30 years old. It is also home of the first Woman’s and Gender Studies program in Europe. Both things I mention because they feed into the demographic and the kinds of people that would gather around and informed the house that I grew up in, which is far from the museum space from which I operate: where “queering the collection” is programmed and diversity taught instead of being the natural fabric of an institution. Before the museum, I worked with and for women my entire upbringing and at Casco in a queer environment, which I took for granted.

One of the things that I’m grateful for working in a museum structure, is that actually you feel the hand of the state at play through the collection. The collection is the proof of the pudding not so much programming and exhibition. Heritage institutions can absolve themselves of responsibility through programming. The public program does not necessarily resemble the underlying structure. We live in this kind of insipid rotation of an exhibition every three or four months. Institutions can always present topical without transforming the back-end. Collections and archives are where the traces of authentic expression lie. A public collection is by default also an extension of the state and its value system, what is held dear and thus made valuable, and what it disregards and excludes. It is also where you’ll find traces of the conditions around works of art as they enter the state collection. This is primarily what I’m interested in, not whether things are included or not, which is quite limiting in its representational position.

Yes, it’s then also about care and truly collaborating with somebody. What happens after a work is part of the collection or before the contract is signed. Can there be another kind of reciprocity than just the money transfer and the CV-mention. What might a collaboration mean if there is a continuation of a relationship. For the material, for the artwork, for the artist(s).

Yes, and maybe it is important to say that in 2021 Research Curator Nick Aikens and I joined the acquisition committee at the Van Abbe, which is also when I realized just how opaque collections and acquisitions processes are to a general public. I think perhaps the single most important issue that Metropolis M puts out is in December when the ‘nieuwe collectieve aanwinsten’ is made public. This is one of the readily available documents where you can judge the lay of the museum land, so to speak. It’s here you also get a kind of sum and measurement of institutions, still qualified in problematic binary ways, they tally male/female ratio in various Dutch museum collections. We don’t put that aside; we continue to problematize it but the schematic of the country is tangible and accessible there.

2021, which of course is the height of the Covid years and is when I worked on A Lasting Truth Is Change, which was not so much a collection exhibition in that I was less concerned about telling an art history of art and brought the collection in dialogue with works outside of the collection around the question of “change” and how we can get in right relationship with, following Octavia E. Butler, lasting change. Around that time different types of institutions were asked to consider what situated practice is, how to work with what’s at hand or immediately around. Covid was for many a tragic thing but also a portal, those things came to the surface. For museums or heritage sites, that meant working with the depot instead of flying-in shows. I got to understand the house that I’m in because that shifted.

You asked me about strategy. A Lasting Truth Is Change shaped my trajectory at the museum, by coming closer to the collection the violence became more tangible and my path became clearer. Out of around 3500 works, we have around 150 female identifying artists in the collection, and I counted under a dozen Black artists, this is not an exception but indicative of the state of museum collections in this part of the world.

Yes, that’s interesting. That shows a whole other perspective and practice.

Yes, you would never guess this from our museum’s programming.

How do you change that? Or do you?

You can’t, not in any substantive way.

This is that constant push and pull, right? Especially when you become part of an institution. You see something, something that you might not agree with and you feel like this could or should be different. Then at the same time, you know that if you focus solely on changing that, it will not only burn you out because of the push-back, it also, simply won’t change. Which is actually saying you’re not going to change the system because that’s what we’re actually talking about. It’s a bigger system. That is then very visible in, for example, the collection strategies. Again, I totally agree with you and it is also often my response to people when they ask me or state that I am there to ‘change’ the institution. No, I’m definitely not under the impression that I will change an institution that has been there for such a long time in a certain form, over a few years. I’m trying to do something interesting there, test out ideas, experiment and enjoy the process while being there, together. I think that might be one of the most ‘radical’ things you can do. Claiming that joy and that space and the people you want to work with. Yet it’s this weird in-between space because of course, I want systems to change.

Yes, I’m also not under the illusion that I’m going to change the institution in any fundamentally significant way. However, I am interested in developing conditions for liberatory work to exist, I also require certain conditions to operate from. I learned to negotiate this, and I do want to stress that these things can be taught and learned. Environmental psychologist Adeola Enigbokan helped me speak my intentions at the museum into daily practice, and more importantly helped to strategize how I can align intentions to my horizon beyond the scope of the museum, as a first and as an only.

I try to make the conditions of the institutions clear to whomever I’m inviting in, I make it a point to try to be as open and clear as possible about the context that I’m inviting someone into precisely because of the way that I like to work and so that they know what’s possible and ….

What isn’t?

Yes, and know what I may be able to do and where I am limited. The majority of the visitors are white seniors who can afford a museum card. That’s the space that we play with. It’s not lost on me that I can do programs a certain way because the rest of the house is programmed a certain way namely the collection display Dwarsverbanden curated by Diana Franssen, Steven ten Thije and Charles Esche. I appreciate their effort toward multisensory exhibition making and working with constituencies to determine the architecture and some of the exhibition’s content and programming. This multisensory and constituent-driven exhibition, attempts to satisfy any audiences, while rooted in position. This makes space for me to be experimental with the temporary exhibitions.

It is also how this Mister Motley series started, what would I have liked to read or know when I was just starting out, the strategies and ways of working, of different people, not edited too much to fit a certain gaze, but a real conversation in which people are generously sharing with you what they are dealing with and how they have dealt with things. Amal Alhaag in the first interview for this series said: ‘always come with a crew’. I have now noticed that that crew can also be, partially, outside of the institution. A crew, a support system that you consult or just hang out with whenever.

Yes, always. I’m always with crew, that is also built into the exhibition and the projects I am steering so not always explicit. Those who know, know.

Also, if you work together with people, how do you do this? You talk to each other; you try to truly listen.

I think maybe my first year I was suffering because I was kind of keeping those that I’m inviting in away from the fuckery of the institution. You burn yourself from doing this and then you are like the bulletproof vest trying to catch so that you don’t taint. This doesn’t work and is very tiring. I learned how to throw a party. Literally and also metaphorically, where you introduce the opposing sides to one another and you let your co-conspirators in on what you’re doing.

Hereby also aiming to go beyond the ego of a single ‘star’ curator but rather doing it together. Inviting others in. Of course, there’s a certain structure and pace that asks quite a lot of knowledge of those structures. It’s not like, you can come in and just do it. However, it would be nice to have different people trying stuff out.

I’m glad you touched on this. Curatorial ego is dangerous. It can be monstrous and damaging.

You don’t see clearly anymore. You should have the space to tap out. However, that’s easier said than done.

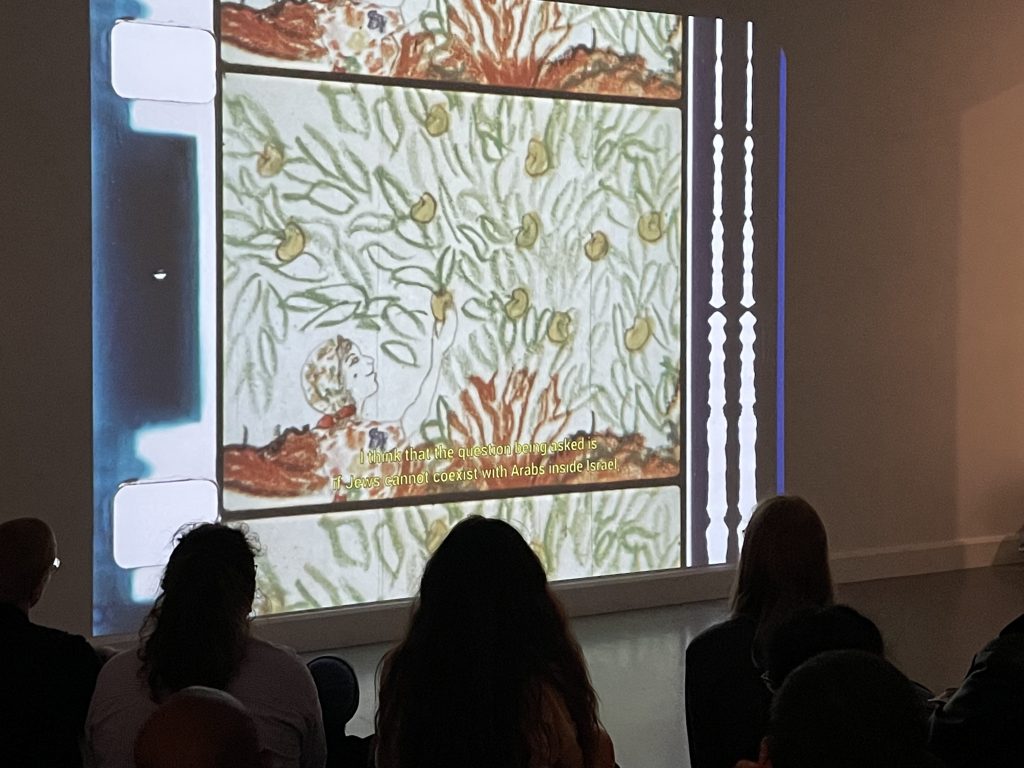

To think of anyone who’s involved in social justice. I mean, there’s plenty of tools and resources about this kind of rotational leadership where one gets to check out and rest and someone else steps in. Black radical thought has been tooling this. Of course, particularly women have been thinking about this for a really long time. The current exhibition I worked on “Everything worthwhile is done with other people” cites American educator and abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba as mantra and practice. This saying became a family idiom for her, and speaks to how we’re intrinsically connected; it is relationships that determine our existence. The exhibition explores concepts of decentralization (the transfer of control of an activity or organization to several members) and relationality or being ‘in relationship’ with human and non-human things and we explored these notions through collective practice and brought together individual and collective practices of artists. I am particularly interested in what becomes possible once have instrumentalize the space of the exhibition to serve the true horizon, if we can cop to the fact that the horizon is not the institution. Like we said, you cannot truly transform the heritage house out of its violence as a first or an only but we can make use of its resources to do our own thing, invest elsewhere, create a space following our own terms and conditions.

With Buro Stedelijk for example, I can make a decision to be closed on the 1st of July because I want to commemorate the abolition of slavery and celebrate the freedom during Keti Koti. I don’t need ‘permission’ to do that. At the same time, Buro is a project. What does it mean to have that space, that temporary space, and how do you make use of it and at the same time be aware of the temporality of it and what that might mean?

Yes, that’s what I was trying to say about front and back end, just exactly like you said, the understanding that front of house is temporary and it is a project. It’s not a stand in for, it doesn’t mean all of a sudden, the museum or the institution understands its colonial history through a one-day commemoration. It’s symbolic. Signifiers, yes, they’re important but have strong limitation. I think, particularly in this country they are often used as stand in for structural change,

At the beginning, you shared that when you were younger, you wish you had a version of this ‘conversation series’, which is also why I agreed to do this.

Yes, that way it’s more relatable and in a way, more vulnerable.

Because conversation is a practice from which to glean how people practice on a day to day. Which at least for me says a lot more about someone. I’m often equally interested if not more interested in an artist’s practice or day to day life. Because that’s where you get a sense of how you can relate to and whether you’re compatible or not.

I hope it can help a little bit. Perhaps you are trying to get a teacher to understand what you’re trying to write or what you’re trying to envision, but they don’t get what you’re doing. How do you not burn yourself out by (over)explaining it to them? Perhaps not explaining is what I propose. Also, here.

There’s so many times I have the urge to yell to everyone: ‘It’s all made up! We can just change this!’ I think like museum gallery spaces, white cube spaces. They have so much authority, but it’s all constructed and made by people so we can shift and change it when it doesn’t serve us. It’s really just that simple. Which seems like rudimentary, basic, but it really isn’t.

It’s a very important thing to realize. That you always have the possibility to opt out. These rules are guidelines, made by people. We can also say, well, no.

That’s tied to that. These guidelines then become tradition and history. That’s where you’ll meet the pushback. However, all of those things are constructed. How we move in space, what we value when it doesn’t serve us, we can change or shift it. It seems like a basic thing to agree on and it is but I think it’s important to return to because once we understand that actually that’s how we can understand, we can change things more significantly in culture and around us to catch up to our imagination of more joyous and equitable ways of being together. We can actually tangibly shift that. We’ve spoken a lot about what’s difficult about working in the sites that we do, but why I think I keep doing it is that it’s a space to exercise some of these things and that’s really beautiful. It is a good way to give hope.