Als kunstenaar voor de klas staan – Interview met Sterre Boerkamp

*English version below

In september 2020 werd het boek Wicked Arts Assignments uitgegeven door Valiz. Het boek werd samengesteld door Emiel Heijnen en Melissa Bremmer, lectoren kunsteducatie van de Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten. Hart van het boek vormen de kunstopdrachten die zijn verzameld van over de hele wereld. Belangrijk is dat deze opdrachten daadwerkelijk eerder door de docent zijn uitgevoerd; het ‘bewijsmateriaal’ hiervan is middels foto’s toegevoegd op de pagina’s naast de desbetreffende opdracht.

Maak een voorwerp waarmee je iets uitbeeldt dat jou kwaad maakt en laat in een filmpje op een toepasselijke manier de vernietiging van het voorwerp zien’ is de Wicked Arts Assignment van Sterre Boerkamp die gepubliceerd is in het gelijknamige boek. De opdracht ontstond vanuit de gedachte dat het overweldigende gevoel van woede vaak geassocieerd wordt met agressie of controleverlies, maar woede kan ook een krachtige emotie zijn die aanzet tot handelen wanneer er iets gebeurt waar je het niet mee eens bent. Sterre voerden de opdracht uit met tweedeklassers in het voortgezet speciaal onderwijs. De leerlingen werden kwaad van alledaagse onderwerpen zoals ‘de kleur paars’ en ‘Nutellapotten die niet open gaan’ en verbeeldden ook hun woede over grotere thema’s die hen een gevoel van onmacht geven, zoals zinloos geweld, de plastic soep en dierenmishandeling. Het maken van voorwerpen die later vernietigd werden werkte bevrijdend voor de leerlingen.

Geïnspireerd door de opdracht, bevragen we Sterre Boerkamp over de vervlechting van haar kunstpraktijk met haar educatieve praktijk en haar interesse om als kunstenaar voor de klas te staan.

Hoe zou je jezelf voorstellen?

Ik ben Sterre Boerkamp, kunstdocent in het voortgezet speciaal onderwijs en illustrator. Ik werk op een middelbare school waar de meeste leerlingen gediagnosticeerd zijn met een vorm van autisme. De school is in heel veel opzichten hetzelfde als een reguliere middelbare school, maar er is meer aandacht voor sociaal emotionele ontwikkeling. Er is meer structuur en kleinere klassen dus meer aandacht voor individuele leerlingen. Dat maakt het voor mij als kunstdocent heel aantrekkelijk, want hierdoor kan ik mijn les goed aanpassen op mijn leerlingen en hun interesses. Naast mijn docentschap volg ik de master Kunsteducatie aan de Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten. Tekenen is voor mij vanzelfsprekend een groot onderdeel van mijn leven. Ik ben altijd aan het tekenen. Het is voor mij een manier om de wereld te vatten, nog voordat mijn gedachten stromen.

Hoe zou je de relatie tussen je kunstpraktijk en je onderwijspraktijk beschrijven?

Al sinds het begin van mijn docentschap ben ik op zoek naar manieren om die twee praktijken in elkaar te verweven: om ook als kunstenaar voor de klas te staan. Zo heb ik bijvoorbeeld in de les altijd meegedaan met alle opdrachten die ik aan mijn leerlingen gaf. Dat brengt een heel andere energie in de klas: rustiger, meer geconcentreerd. Wanneer je lesgeeft ben je vaak meer naar buiten gericht, terwijl als je zelf iets maakt, meer een intern proces ervaart. Leerlingen kunnen ook een beetje afkijken. Ik laat zien dat het maakproces ook voor mij als docent een ontdekkingsreis is, wanneer bijvoorbeeld ineens iets mislukt, of als ergens een klodder zit die ik niet wil. Door samen dit creatieve proces te doorlopen, creëer ik meer aansluiting en gelijke grond met mijn leerlingen.

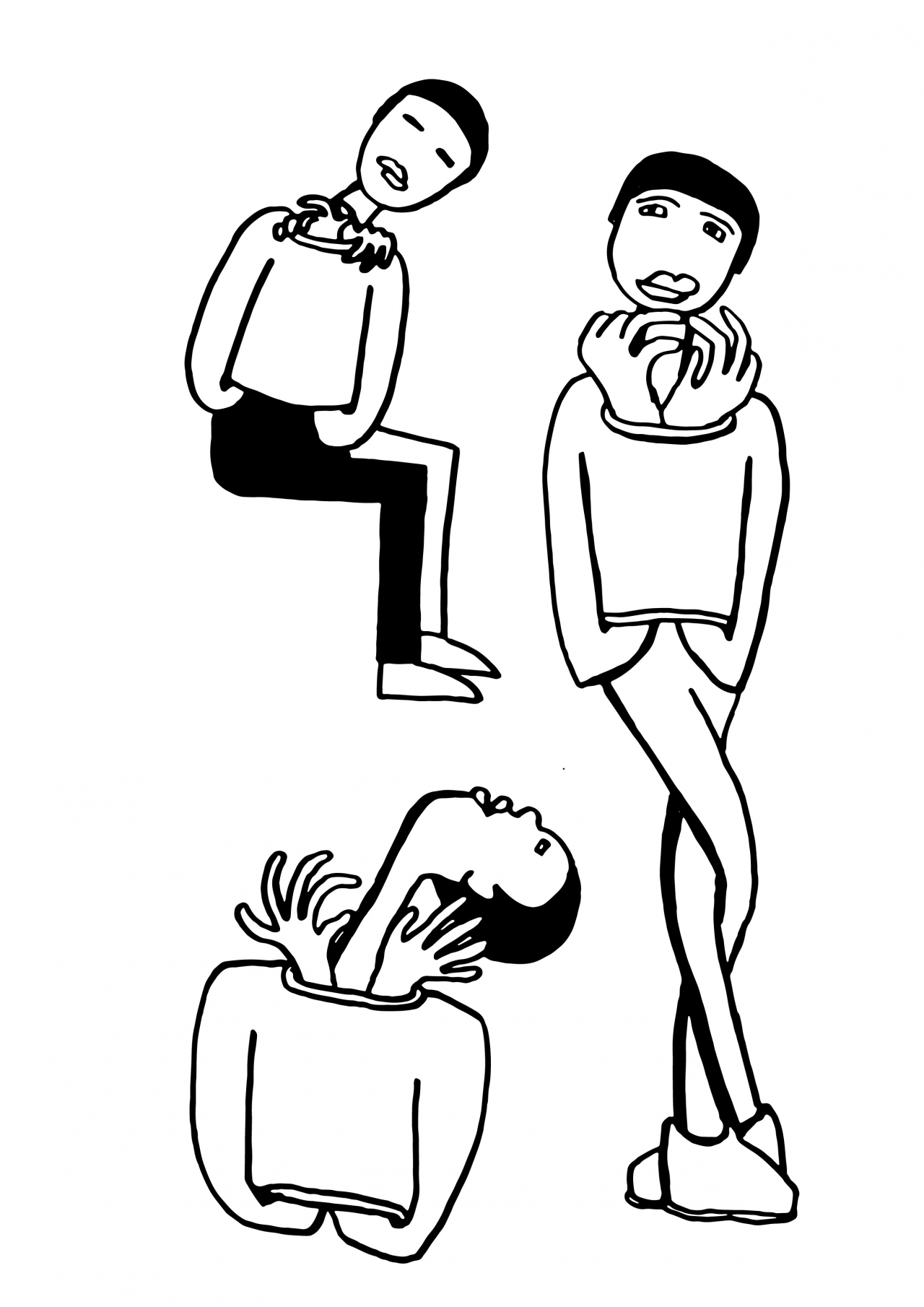

Ik heb een periode gehad waarin het docentschap zoveel van mij vroeg, dat ik thuis nauwelijks toekwam aan tekenen. Daarom ben ik in de klas gaan tekenen, want daar was ik tenslotte de hele dag. Ik schetste een soort cartoons van situaties die zich voordeden in de les. Al tekenend tussen de leerlingen maakte ik via de tekeningen op een andere manier contact met hen. Zij gingen zich bemoeien met wat ik tekende en gaven hun ongezouten mening. Waar ik bijvoorbeeld veel commentaar op kreeg waren de uiterlijke kenmerken van medeleerlingen. Hoe ik het haar tekende: te kort, te lang, welke kant het opzit. Of: lijken die schoenen wel goed genoeg? Ik kreeg veel tips over hoe ik dat beter kon doen. Ik vond dat heel leuk, dit soort directe feedback kreeg ik niet vaak. Het motiveerde mij om mijn tekeningen te verbeteren.

Wat vind je belangrijk in je docentschap in relatie tot je leerlingen?

Lesgeven blijft voortdurend een zoektocht, zeker wanneer je samen kunst maakt. Mijn leerlingen vinden dat soms best moeilijk. Ze moeten ineens iets helemaal uit zichzelf halen. In plaats van een duidelijke instructie, zijn daar ineens heel veel zijsporen die je kunt nemen. Dat brengt onzekerheid met zich mee. Groepsprocessen zijn erg bepalend voor hoe leerlingen zich voelen, zeker in het speciaal onderwijs. Het is daarom erg belangrijk om als docent aan te voelen: Wat heeft deze groep op dit moment nodig? Wat is haalbaar? Hoe creëer je een veilige sfeer? Van dat soort basisvoorwaarden moet je je voortdurend bewust zijn.

Ik vind het interessant om een klas echt als een groep te zien. Dat klinkt als een open deur, maar ik denk dat het onderwijs veel gericht is op individuele opdrachten. In zo’n groepsproces heb je een regisseur nodig, dat vind ik een interessante rol om mee te spelen als docent. Samenwerken is nog best een uitdaging, zeker voor leerlingen met autisme. Sommigen kunnen zelf groepjes maken, anderen hebben daar meer hulp bij nodig. Hoe kun je vragen of iemand met jou wil samenwerken? Dat is iets waar je in het speciaal onderwijs gewoon veel meer mee bezig bent. Ik geloof in samenwerken, voor alles in het leven moet je samenwerken dus dat is ontzettend belangrijk om al op jonge leeftijd mee te oefenen. Daarnaast is het ook leuk, want als je samenwerkt kom je weer op nieuwe ideeën. Juist die dialoog is waardevol.

In een recent project maakte ik met twee groepen een stop-motion film. Het onderwerp was: na de dood. Zo’n onderwerp gaat echt ergens over en is voor mij ook een manier om erachter te komen hoe zij denken over van alles. Met de ene groep heb ik gebrainstormd en ideeën in kaart gebracht waar de film over zou kunnen gaan. Ze hadden allerlei ideeën over de dood en hoe het hiernamaals eruitziet. Samen hebben we een scenario uitgewerkt en met de andere groep ben ik die stop-motion film helemaal gaan maken. Het maakproces verliep heel organisch: in het begin kwamen leerlingen steeds naar mij toe met ieder idee, maar na verloop van tijd veranderde de dynamiek en merkten ze: hé, ik kan dit ook met een klasgenoot oplossen, daar heb ik niet per se een docent voor nodig. Leerlingen zijn vaak heel trots wanneer ze iets concreets gemaakt hebben zoals een echte film of een gezamenlijke muurschildering. Dat geeft een gevoel van eigenaarschap. En juist omdat het dan ook echt iets groots en moois heeft opgeleverd, kunnen ze zichzelf ermee verbinden.

Wat vind je belangrijk in je samenwerkingen met anderen?

Door mijn eigen ervaring als student bij de Master Kunsteducatie leer ik mensen kennen uit alle disciplines: van beeldende kunst tot muziek, theater en dans. Door interdisciplinaire samenwerkingen kom ik in aanraking met ander taalgebruik en een ander referentiekader. Dat is heel inspirerend! Een van de initiatieven die ik samen met mijn medestudenten opzette tijdens de lockdown is de website lockdownlessen.nl. De site biedt een verzameling van kunstlessen, in tijden van sociale afstand.

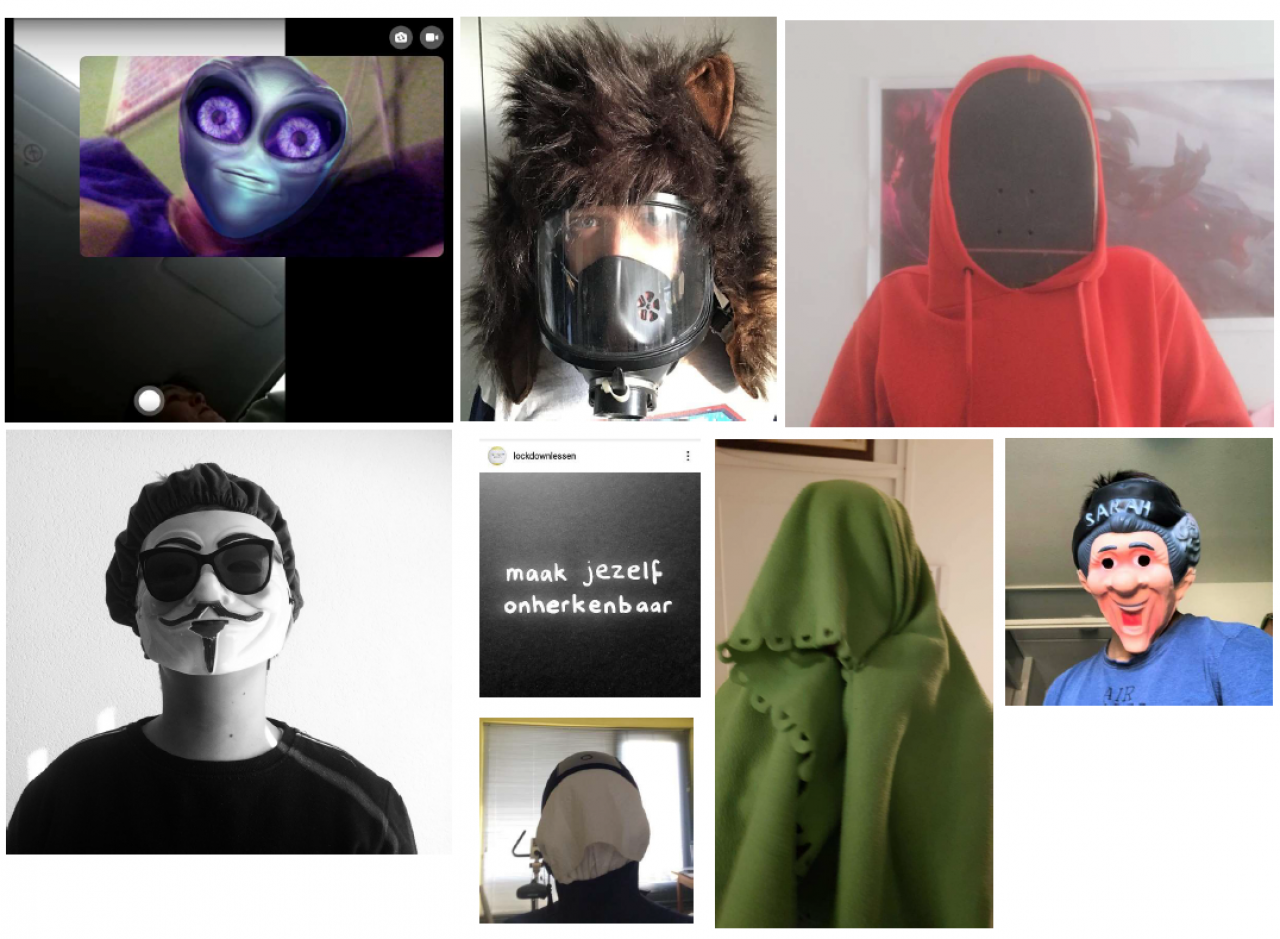

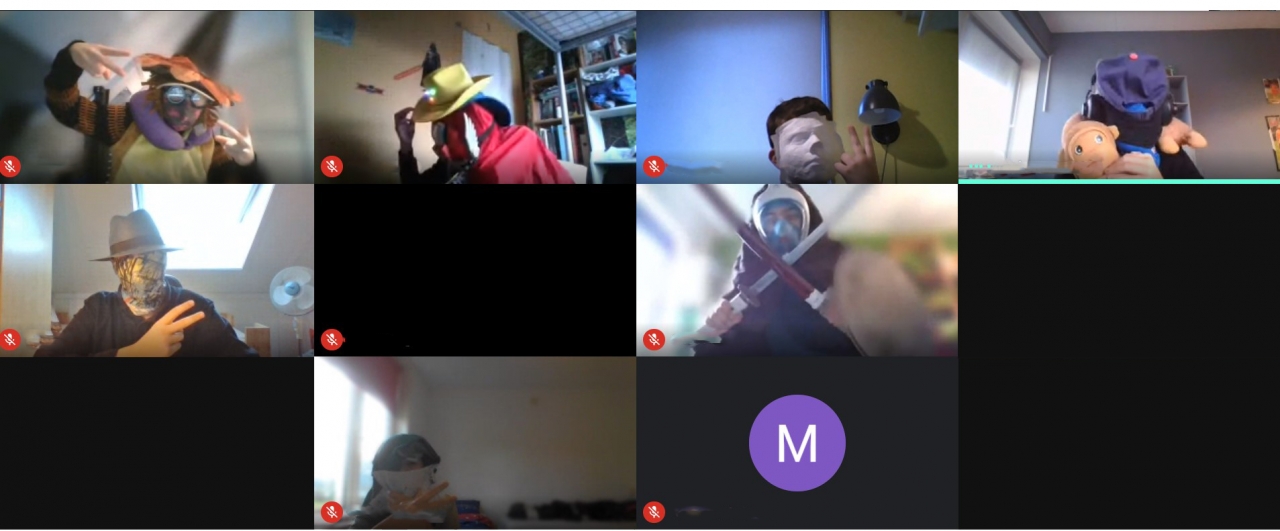

Samen met mijn studiegenoot Channa de Vries ben ik het project Lockdown Challenges gestart. Deze challenges dagen uit om ‘quarantaine kunst’ te maken: kunst waarbij gewerkt wordt met materialen die iedereen thuis voor handen heeft. Dat was echt een schot in de roos: opdrachten die door de leerlingen zelf werden bedacht, en ook door hen werden uitgevoerd. Het leverde hele interessante dingen op. De challenge: ‘maak een foto van je huisdier op een gekke plek’ resulteerde in 50 foto’s van huisdieren of knuffels op de meest gekke plekken, allemaal in hun huis. Het begon als een heel ludiek en luchtig idee, maar als je dan de verzameling van al die verschillende uitvoeringen ziet, ontstaat er een betekenisvol beeld. De beelden waren veelzeggend over de persoonlijke leefomgeving van de leerlingen: knuffels hangend aan de deurpost, in een lamp, een kat in een doos naast het bureau waar huiswerk wordt gemaakt: de verveling en soms ook eenzaamheid werd hierdoor zichtbaar. Met het delen van deze foto’s op Instagram kregen de leerlingen een podium om hun alledaagse ervaringen in corona-tijd op een artistieke manier te uiten.

Welke inspiratiebronnen, educatief, artistiek of theoretisch, hebben jouw manier van denken over je praktijk beïnvloed?

Ik ben geïnteresseerd in kunstenaars die net als ik ook met groepen werk maken. Melanie Bonajo bijvoorbeeld maakt films met groepen ouderen of kinderen, waarmee ze reflecteert op de wereld om ons heen. Dat levert hele mooie dingen op, speels maar ook met veel diepgang. Ze behandelt de kinderen met wie ze werkt heel gelijkwaardig. Ze ziet ze echt als bron van wijsheid en volwaardige mensen, die met een eigen blik naar de wereld kijken. Het lijkt me echt fantastisch om dat soort projecten ook te doen met mijn leerlingen.

Ik leer veel van mijn leerlingen. Bijvoorbeeld in het project Anger control, dat in het Wicked boek staat, over woede en vernietiging. Deze opdracht is geïnspireerd op Doug Aitken’s installatie The Living Garden, waarin hij de manier waarop wij mensen ons verhouden tot de natuur om ons heen bekritiseert. In de installatie heeft hij de verhouding omgedraaid: bezoekers mogen vrijelijk met een honkbalknuppel hun woede uiten op het interieur dat door mensenhanden gemaakt is, terwijl de jungleplanten rondom de installatie veilig achter kogelvrij glas staan. Dit soort kunst is voor mijn leerlingen vaak nieuw, maar ze kunnen de achterliggende gedachte ontcijferen. Het van gedachten uitwisselen met jongeren die je niet altijd makkelijk bereikt is erg bijzonder.

Kun je een voorbeeld noemen van een kunstopdracht of ervaring die grote indruk op je heeft gemaakt?

Ik ben een groot fan van Stichting Buitenkunst. Op een buitenlocatie geven professionele kunstenaars diverse kunstworkshops aan deelnemers, die ook kamperen op het terrein. Wat ik daar zo goed aan vind, is de spontaniteit: mensen die de lessen geven doen dat vanuit hun eigen fascinaties als kunstenaar, niet vanuit vooraf geformuleerde leerdoelen. Die openheid, daar ben ik zelf ook naar op zoek in mijn eigen werk. Het gaat op een heel speelse manier, het is een experiment voor zowel de deelnemers als voor de docent. Dat maakt het zo’n unieke ervaring. Afhankelijk van de groep en de sfeer ontstaat er dan soms iets in het moment. Dat hoeft niet groots en meeslepend te zijn, het kan juist iets heel kleins zijn en dan toch heel veel opleveren. Wat dat precies is, is heel lastig te vangen. Mijn ervaring als deelnemer van Buitenkunst brengt mij een heel groot gevoel van vrijheid. De mogelijkheid om een uitstapje maken naar onbekend terrein, je over te geven en te gáán. Het uit je comfortzone stappen is ook eng, het maakte me bewust van wat ik dagelijks van mijn eigen leerlingen vraag als docent.

Wat definieert een goede kunstopdracht?

Ik denk dat het belangrijk is dat leerlingen de regie hebben over wat ze aan het doen zijn. Dat is iets wat bij mij ook wel eens misgaat. Soms is een opdracht te abstract of te conceptueel. Ik heb wel eens gehad dat leerlingen braaf gingen doen wat ik van ze vroeg, maar dat ze zelf eigenlijk geen idee hadden van wat ze deden en waarom. Ik realiseerde me daardoor dat het niet alleen gaat om iets moois maken of heel veel talent hebben, maar dat het er bij kunst vooral omgaat dat je ideeën krijgt en dat je ideeën kan uiten. Dus dat is wat voor mij een goede opdracht maakt. Dat je die ruimte biedt zodat de leerlingen verbindingen kunnen leggen tussen de opdracht en hun eigen wereld. Dat ze het zich eigen kunnen maken. Dan komt er energie in en maken ze vaart!

——————————-

Teaching as an artist – Interview with Sterre Boerkamp by Sanne Kersten

‘Make an object that represents something that makes you angry. Then make a short film that shows its destruction in a fitting manner’ is the Wicked Arts Assignment by Sterre Boerkamp, published in the book of the same name. The assignment was born from the idea that the overwhelming feeling of anger often is associated with aggression or loss of control; however, anger can also be a powerful emotion that triggers an action when something bothers you. Boerkamp carried out the assignment with second-graders in secondary special education. The pupils were upset with everyday topics such as ‘the color purple’ and ‘Nutella jars that won’t open’. They also depicted their anger towards larger themes that made them feel helpless, such as random acts of violence, plastic pollution in the oceans, and animal abuse. Making objects that were later destroyed was liberating for these youngsters.

Inspired by the assignment, we have a conversation with Boerkamp about the intertwining of her art practice with her educational practice, and her interest in teaching as an artist.

How would you introduce yourself?

I am Sterre Boerkamp, an art teacher in secondary special education and an illustrator. I work at a secondary school where most pupils are diagnosed with some form of autism. In many ways the school functions the same as a regular secondary school, but there is more focus on social-emotional development. There is more structure and the classes are smaller, so more attention can be paid to individual pupils. These circumstances make it very attractive for me to work as an art teacher, because they allow me to adapt my classes to my pupils and their specific interests. In addition to my teaching practice, I’m studying at the Master of Education in Arts at the Amsterdam University of the Arts. Drawing is a big part of my life. I’m always drawing. It’s a way for me to grasp the world, before my thoughts start flowing.

How would you describe the relationship between your art practice and your teaching practice?

Ever since I started teaching I have been looking for ways to interweave these two practices, to teach as an artist. For example, I always participated in the assignments I gave my pupils. That brings a completely different energy to the classroom: calmer, more concentrated. When you teach you are often more outward-looking, but when you make something yourself, you experience more of an internal process. Pupils can also copy a little. It allows me to show that the creative process is still a journey of discovery also for me as a teacher, for instance when something suddenly fails, or when there is a blob somewhere that I don’t want. By going through this creative process together, I create more connections and level ground with my pupils.

I went through a period when being a teacher asked so much of me that I hardly got around to do any drawing at home. That’s why I started drawing in class, because after all, I was there all day. I drew cartoons of situations that occurred right there. While drawing in class, I made contact with my pupils in a different way. They interfered with what I was creating and gave their unvarnished opinion. For example, I received a lot of comments on the appearance of fellow pupils. How I drew the hair: too short, too long, which way it faced. Or: do those shoes seem good enough? I got a lot of tips on how to make certain things better. I liked that: I didn’t get this kind of direct feedback very often. It motivated me to improve my drawings.

What do you find important in your teaching practice in relation to your pupils?

Teaching is always a quest, especially when you make art together. At times, my pupils find making art quite difficult. Suddenly they have to make something from nothing. Instead of clear instructions, there are a lot of sidetracks you can take. It brings a kind of uncertainty. Group processes are very decisive for how pupils feel, especially in special education. Therefore it is very important to get a sense of what a group needs at that moment. What is feasible? How do you create a safe atmosphere? You need to be constantly aware of those kinds of basic conditions.

I find it interesting to see a class as a group. That sounds obvious, but I think that education focuses a lot on individual assignments. In a group process, you need a director, which I find an interesting role to play as a teacher. Working together is still quite a challenge, especially for youngsters with autism. Some can form their own groups, others need more help. How do you ask someone if they want to work with you? That is something you need to pay much more attention to while teaching special education classes. I believe in working together – it is necessary for every aspect of your life, so it is very important to practice at a young age. It’s also fun because working together can result in new ideas. It’s this dialogue that’s so valuable.

In a recent project, I made a stop-motion film with two groups. The topic was ‘after death’. It’s not a light-hearted topic, and for me it is also a way to find out how my pupils feel about these things. With one group I brainstormed and mapped out ideas of what the film could be about. They had all kinds of thoughts on death and what the afterlife looks like. We worked out a scenario together and I started making a stop-motion film with the other group. The creative process was very organic: in the beginning, pupils kept coming to me with every idea, but over time the dynamics changed and they noticed: hey, I can also solve this with a classmate, I don’t necessarily need my teacher for this. Pupils are often very proud when they have made something concrete, such as a real film or a collective mural. It gives them a sense of ownership. And because it has resulted in something great and beautiful, they can connect themselves with it.

What do you find important in your collaborations with others?

Through my own experience as a student at the Master of Arts in Education, I get to know people from all disciplines: from visual arts to music, theater, and dance. Through interdisciplinary collaborations, I encounter different uses of language and a different frame of reference. That’s very inspiring! One of the initiatives that I set up together with my fellow students during the lockdown is the website lockdownlessen.nl. The site offers a collection of art assignments that can be used in times of social distancing.

Together with my fellow student Channa de Vries I started the project Lockdown Challenges. These challenges invite you to make ‘quarantine art’: art that works with materials that everyone has at home. It really hit the mark: these were assignments that were devised by the youngsters themselves, and were also carried out by them. The outcome was very interesting. The challenge ‘Take a picture of your pet in a weird place’ resulted in fifty photos of pets or stuffed animals in the craziest places, all in their homes. It started out as a very playful and light-hearted idea, but when you see the collection of all those different versions, a meaningful image emerges. The photo’s revealed a lot about the personal environment of the pupils: stuffed animals hanging from the door frame, in a lamp, a cat in a box next to the desk where homework is done. Boredom and loneliness became visible as a result. By sharing these photos on Instagram, the pupils had a stage to express their everyday experiences during the pandemic in an artistic way.

What sources of inspiration, educational, artistic, or theoretical, have influenced the way you think about your practice?

I am interested in artists who, like me, make collective works. Melanie Bonajo, for example, makes films with groups of elderly or children, reflecting on the world together. The outcome is incredible: playful, but also with a lot of depth. She treats the children she works with as equals: she really sees them as sources of wisdom, as full-fledged people, who look at the world in their own unique way. I think it would be fantastic to do those kinds of projects with my pupils.

I learn a lot from my pupils, for example with the project Anger control, which is in the Wicked book, about anger and destruction. This assignment was inspired by Doug Aitken’s installation The Living Garden, with which he criticizes the way we humans relate to nature. In the installation, he reversed the roles of men and nature: visitors can freely express their anger at the man-made interior with a baseball bat, while the jungle plants around the installation are safely hidden behind bulletproof glass. This kind of art is often new to my pupils, but they do understand the concept behind it. Exchanging ideas with young people who are not always easy to reach is very special.

Can you give an example of an art assignment or experience that made a big impression on you?

I am a big fan of the Buitenkunst Foundation. At an outdoor location, professional artists give various art workshops to participants who also camp on site. What I like about that is the spontaneity: the people who teach the classes do so based on their own fascinations as artists, not based on pre-formulated learning goals. I aim for that kind of openness in my own work. It is done in a very playful way, it is an experiment for both the participants and the teacher. That’s what makes it such a unique experience. Depending on the group and the atmosphere, sometimes something arises in the moment itself. It doesn’t have to be big and compelling, it can be something very small and yet yield a lot. It’s very hard to pin down exactly what that is. My experience as a participant of Buitenkunst brings me a great sense of freedom: the opportunity to take a trip into unknown territory, surrender and go. Stepping out of your comfort zone is scary, it makes me aware of what I ask of my own pupils every day as a teacher.

What defines a good art assignment?

I think it is important that pupils are in control of what they are doing. It’s not something I always succeed at. At times, an assignment is too abstract or too conceptual. I have had pupils do what I asked them to do, only to find out they had no idea of what they were actually doing and why. This made me realize that it’s not just about making something beautiful or having a lot of talent, but that art is mainly about generating ideas and being able to express them. So that’s what defines a good assignment for me: to offer a space where pupils can make connections between the assignment and their world, making it their own. Then energy comes into play and they get to full speed!