The urge to measure

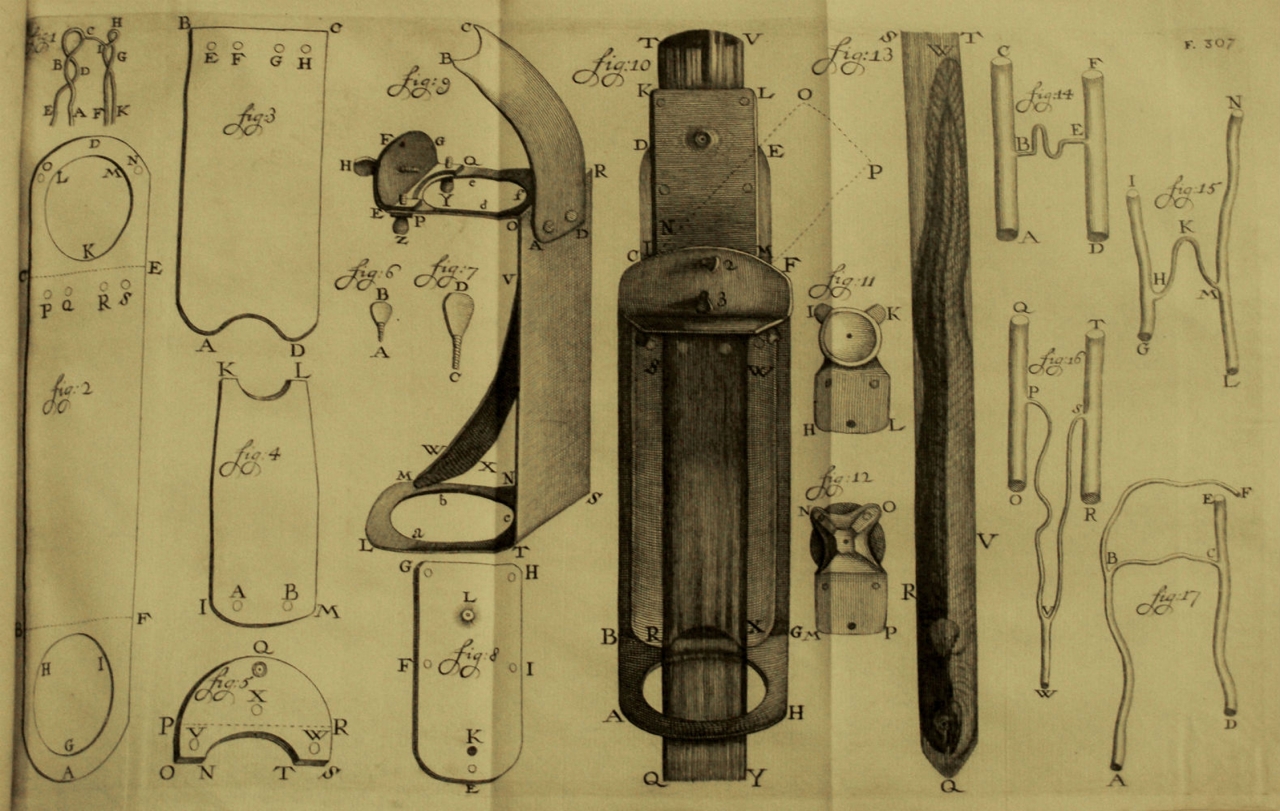

The urge to measure and categorize information is an inherent part of being human. Instruments for measuring are among the earliest tools ever invented by humans, and one could even say that weights and measures are one of the necessities of life. They are essential for a wide range of activities such as navigating, building and trading; activities considered to be at the foundation of our modern life. Not only are weights and measures key to engineering, science, physics and economics; they are our world, because everything has mass and takes up volume and space. In order to live in our physical world, we need to understand it and measuring is key to the knowledge of and interaction with our surroundings. Furthermore, the dominant belief of Western culture is that numbers are equivalent to reality. If you can put a number to it, you can make it real. Once made real, it’s yours to manage and control.

Not being able to quantify something can have an effect that reaches far into our understanding of the world. For instance, the number zero as a concept is relatively new to us. Although invented earlier in different places in the world, it only arrived in Western Europe in the 12th century AD. Before this time of course people knew when they had nothing, but there was no mathematical number, no symbol, to represent and communicate it.

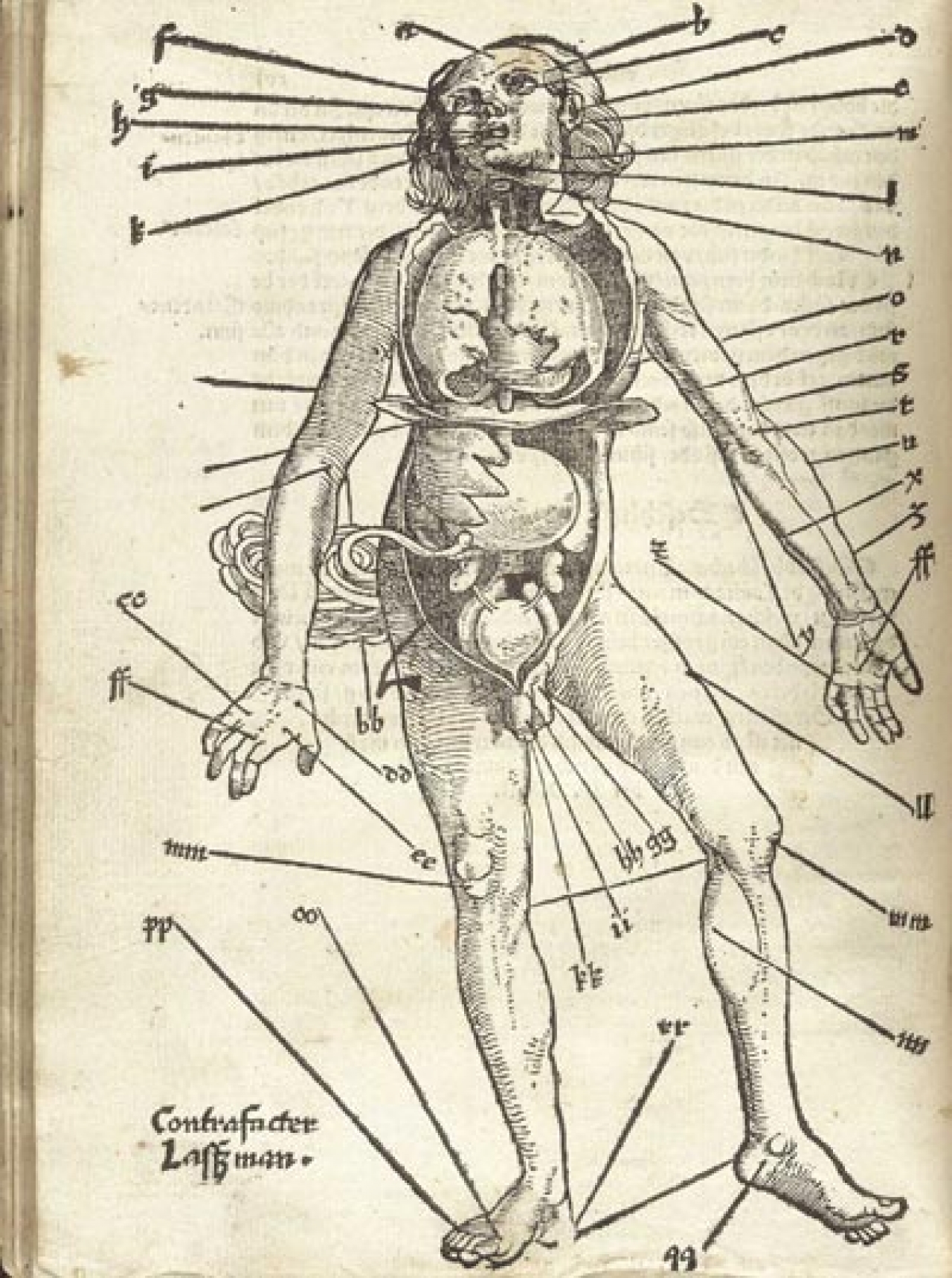

What this example shows so clearly, is that our metric system is an intellectual concept, not a natural given. History shows us that we have had many different kinds of measuring devices and standards that have changed over time. Often older systems of measurement were based on our bodies: we still count in units of ten, because we have ten fingers, but the Mayans for instance counted in units of twenty, because they also counted their toes. The Wurundjeri aboriginals in the south of Australia named their numbers after parts of the body: for instance the shoulder joint meaning 11, and the earlobe referencing the number 14.

The differences between our own modern measuring units and that of the Mayans and the Wurundjeri show us that the way we measure the world, the systems we come up with to make sense of it all, tell as much about the world around us as about ourselves. Counting your toes as well as your fingers suggests a different relation to the body, one more holistic and less focused on the brain. Therefore, did the Mayans count in units of twenty, or the Wurundjeri with their whole body, because they experienced their bodies in a different way, or was this understanding influenced by the way they counted? We make tools and objects to understand the world around us based on our own view of the world, but this subjectivity goes both ways and through our self-made constructions we also define ourselves.

Similar to tools of measurement, artworks can function as a means to understand our surroundings better. We consider them in relation to our physical and cultural selves, and just like measuring tools, they define us as much as we define them. Objects and images don’t just contain meaning, they also create and project it, and seeing, just as measuring, is an act that should never be taken for granted.